- About

- Library

-

Essays

Eric Dinerstein William C. Young

- Plants

- Birds

FIELD NOTES FOR TANZANIA

February 26 - March 27, 2015

William Young

INTRODUCTION

ITINERARY

BIRDS

MAMMALS

REPTILES AND AMPHIBIANS

FLORA

OTHER WILDLIFE

GENERAL IMPRESSIONS

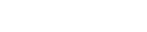

INTRODUCTIONIn 2015, I went on a month-long safari to Tanzania with my friend Martin Van Tol from England. We met up in Dar es Salaam on February 26 and flew home on March 27. In between, we covered more than 3,700 kilometers, or 2,300 miles.

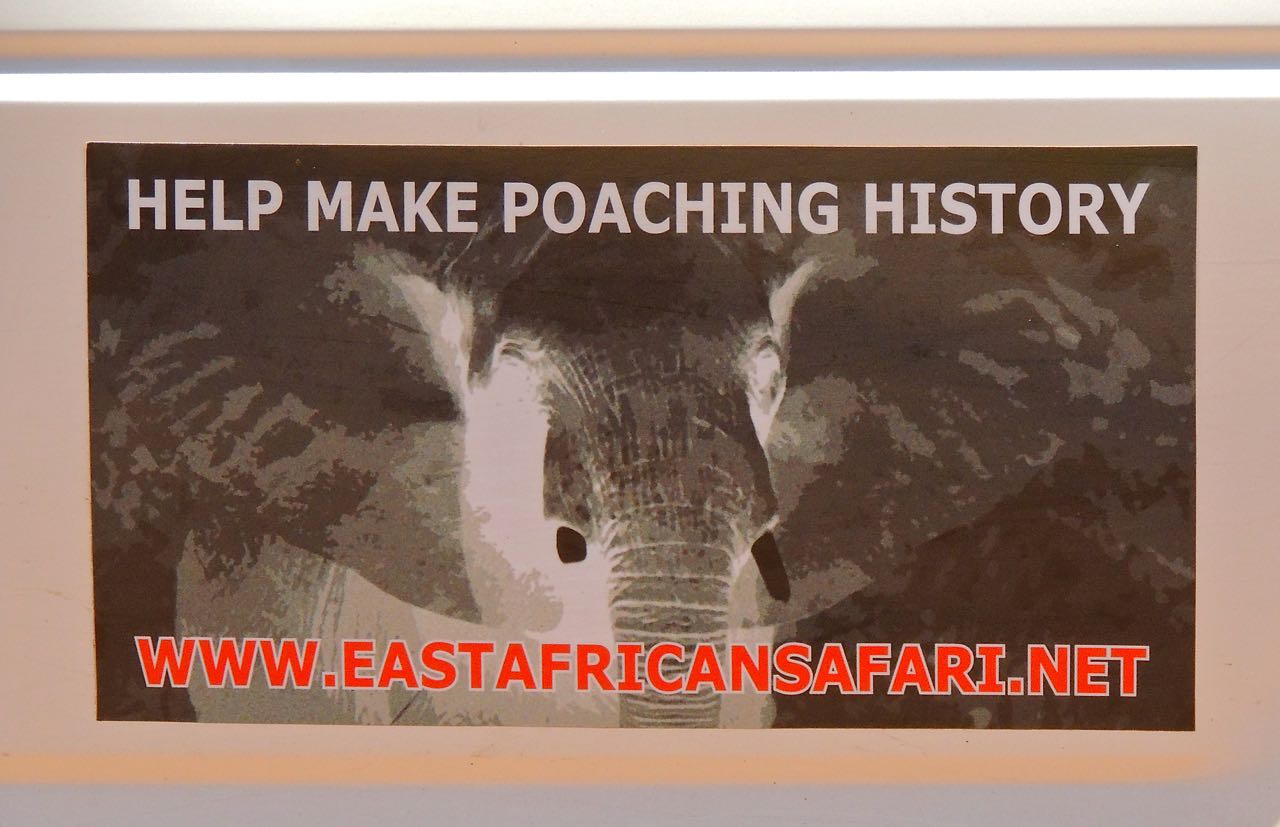

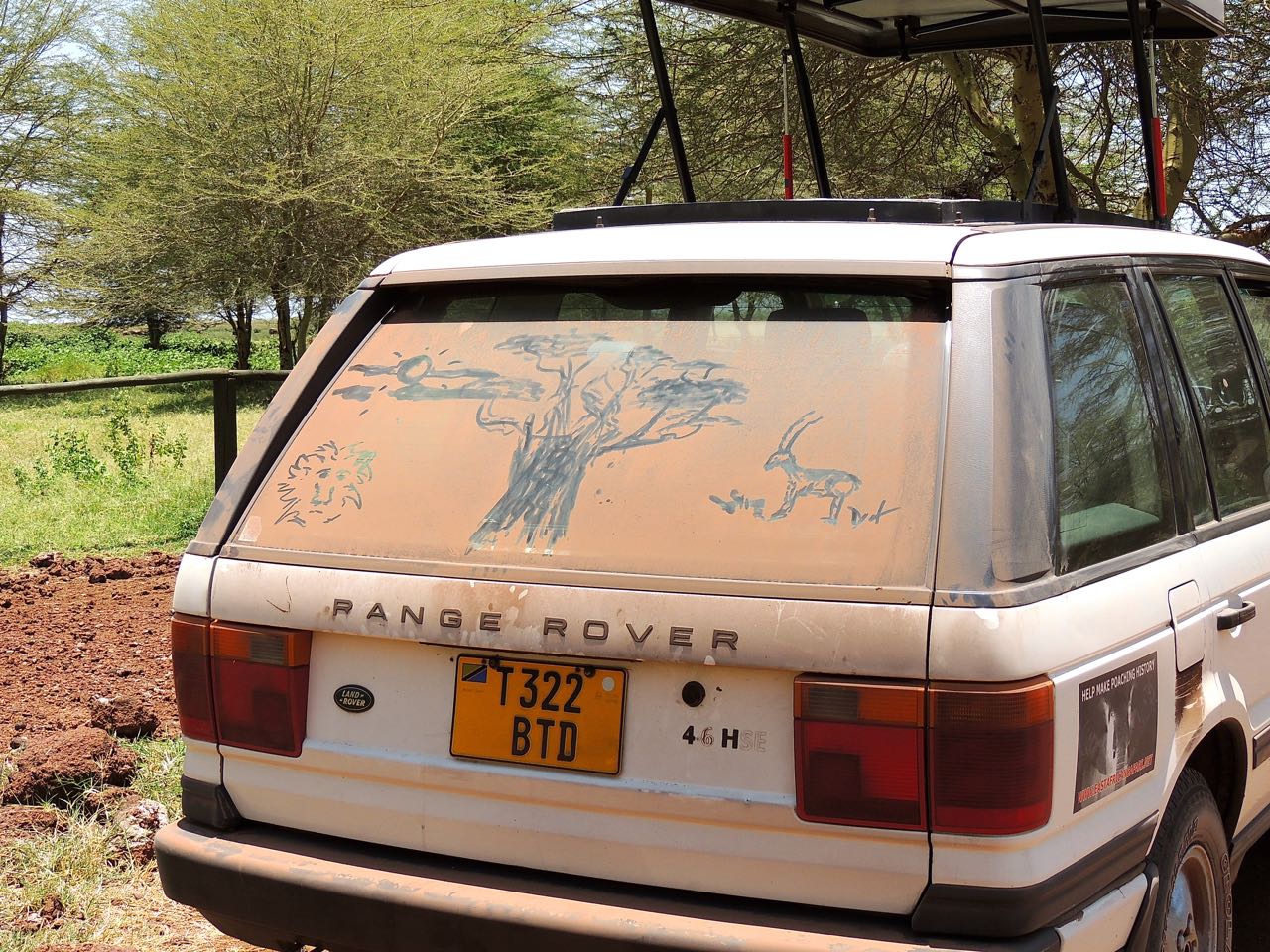

I first met Martin in 2012 on a birding trip to Panama. We arranged the Tanzania trip in August, 2014, through the East African Safari and Touring Company in Arusha. Our guide for the entire trip was Bernard Shirima, who knew a lot about birds and Tanzanian wildlife. He was an excellent and caring companion throughout. During the trip, the three of us managed to see or hear about 455 species of birds and more than 50 species of mammals. In some areas, we also used local guides. We stayed many of the nights in tented camps, and the food was excellent almost everywhere we stayed. This was my first trip to Africa. Martin had been to Africa before, but not Tanzania.

ITINERARYI left Washington, DC, on February 25, changing planes in Addis Ababa on my way to Tanzania. I arrived in Dar es Salaam in the early afternoon on Thursday, February 26. The temperature was in the mid to high 90s — quite a change from the 25 degree weather when I left from Dulles Airport in Virginia the previous day. I went to the Peacock Hotel, where we stayed for two nights. Martin had arrived in the morning and was sitting in the lobby when I got there at about 2:30. I was wearing a cap with a rhinoceros on it from the environmental group RESOLVE — the cap had been given to me by a couple of friends in Washington who work with the organization. Even before I had checked in, a surprised looking man in the lobby came up to me and asked where I had gotten the cap. He was there with two other people who work for RESOLVE and was surprised to see someone wearing one of their caps. He knew my two friends well and said they had just been in Tanzania the previous week.

Friday the 27th was supposed to be a day to rest and become acclimated. Martin and I both felt fine, so we decided to do a birding trip around Dar es Salaam, arranged by our tour company. Our driver was Robert, who worked for the company. He was accompanied by Elizabeth, who is the niece of the company's owner. Among the places we stopped were Ndege Beach, Coco Beach, Tegeta, Mbezi Beach, and Mbweni. Dar es Salaam is a very large city in terms of land area and population, and we never left the city on Saturday. The areas we visited were all north of our hotel, and some were along the edge of the Indian Ocean. We also drove through the beautifully manicured area of the city where many foreign embassies are located. This area looked very different from the rest of Dar es Salaam.

Itinerary - Photo by William Young

Itinerary - Photo by William YoungOn Saturday the 28th, we flew from Dar es Salaam to Mwanza, which is about 530 miles away on Lake Victoria. We stayed at a lovely resort called Serenity on the Lake and were the only guests there. We were told to keep our doors closed, because bats are attracted to the lights and might come in. The next morning, we drove a short distance to a different part of the lake and explored the area by boat. Lake Victoria is the second largest freshwater lake in the world, behind only Lake Superior in the US. John Speke, a British explorer in the mid-1800s, is believed to be the first European to travel to the lake. The African name for the lake is Nyanza, which means "lake," just as Sahara means "desert." There used to be an estimated 100 species of fish in lake, but Nile Perch have killed a lot of species so that there are now only a third as many. The lake also has a lot of water hyacinths, an introduced species that has caused problems for people who fish.

Lake Victoria - Photo by William Young

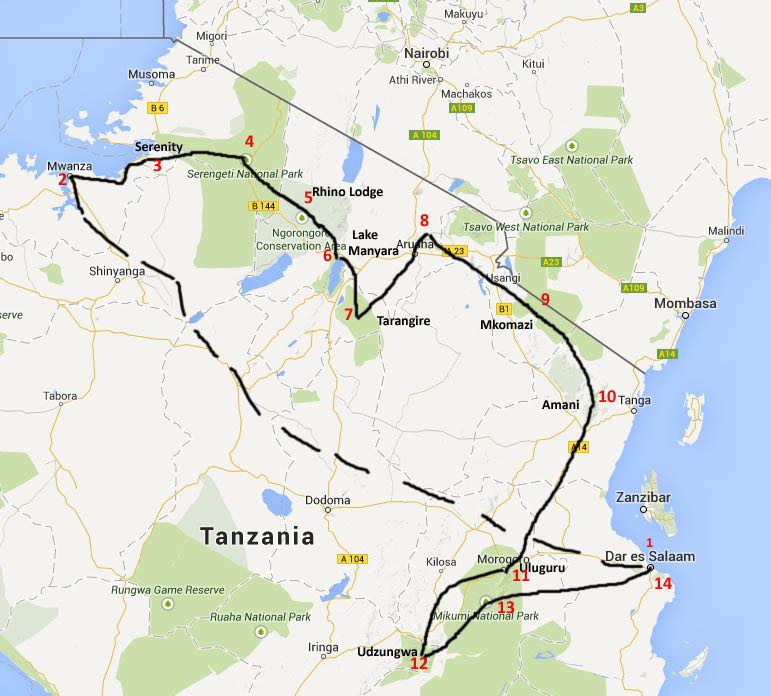

Lake Victoria - Photo by William YoungAfter lunch, we left for Serengeti National Park. After exploring part of the park, we drove 70 kilometers to the Mbalageti Luxury Camp, another pleasant facility, although our rooms were located a long way from the reception area. The chandelier in the reception area was made of animal bones. The rooms were on permanent stone floors and had plumbing facilities, but they had canvas walls. As in some of the places we stayed, the electricity was powered by a generator that did not operate for 24 hours. We had electricity until 11 pm, and it did not come on again until the morning. There were a few other guests while we were there. We were not allowed to go anywhere on the grounds unless accompanied by a guard. Printed material in each of the tents warned guests about elephants and other wild animals. There also was an information sheet to advise how to act around baboons.

We spent a full day at Serengeti National Park on March 2. The Serengeti is part of the ecosystem (35,000 square kilometers) that includes the Maasai Mara in neighboring Kenya. The park itself is 14,763 square kilometers. The name "Serengeti" is derived from "siringit," the Maasai word for "endless plains". The park features an annual migration of more than 1.5 million wildebeest, zebras, and associated predators. We stayed that night and the next at a campsite at Ndutu, which is operated by the Maasai. A woman named Chris was staying there only for our the first night, after which she was going to Arusha to work in an orphanage. I gave her a stack of postcards and notecards to give to the children.

Ndutu Campsite - Photo by William Young

Ndutu Campsite - Photo by William Young Ndutu Campsite - Photo by William Young

Ndutu Campsite - Photo by William YoungOn March 3, we visited Ndutu National Park, which is part of the Ngorongoro Wildlife Area. The park has some greenery, but the area we drove through to get there was dry and barren. On March 4, we birded around the campsite, which had a lot of birds.

On March 5, we drove to Olduvai Gorge and made a brief stop at the museum that showed some of the discoveries Louis and Mary Leakey had made there. The Leakeys found out about the area through German colleagues. A German neurologist who was doing research about sleeping sickness went to the area and noticed many fossils. He told researchers in Germany, and they told the Leakeys about it. We spent the next two evenings at the Rhino Lodge, which was one of the more upscale places we stayed. The room was quite comfortable, but we had electricity for only four hours a night. We spent March 6 exploring the Ngorongoro Crater. The Ngorongoro Conservation Area is 8,300 square kilometers of land that surround the 210 square kilometer crater and adjacent highlands. The crater was once the headquarters of Serengeti National Park, of which it was a part. In 1956, after intense pressure and lobbying from the local Maasai community who were dispossessed of the lands when the national park was set up, Ngorongoro was designated a conservation area. The wildlife is dispersed among an amazing array of ecosystems within the natural amphitheater created by the 600 meter high cliffs around it. It is home to most of the large East African mammals, except the giraffe (the walls are too steep) and impala. The crater has the highest density of lions in Africa, with more than 30 per 100 square kilometers, compared to the Serengeti which has about 14. On the drive from Ngorongoro back to the Rhino Lodge, the vegetation was much greener than anything we had seen to that point.

Olduvai Gorge - Photo by William Young

Olduvai Gorge - Photo by William Young Olduvai Gorge Museum - Photo by William Young

Olduvai Gorge Museum - Photo by William Young Rhino Lodge - Photo by William Young

Rhino Lodge - Photo by William Young Ngorongoro Crater - Photo by William Young

Ngorongoro Crater - Photo by William YoungWe left the Rhino Lodge at 9:30 on the 7th and headed for Lake Manyara. The lake's name comes from the Maasai word "manyara", which is a plant whose common names include firestick plant, Indian tree spurge, naked lady, pencil tree, pencil cactus, sticks on fire, and milk bush. The Maasai use this plant to grow livestock stockades, eventually producing a stock proof hedge which is more durable than those built of thorn. We had planned to stay near Lake Manyara overnight, but we changed our plans due to the drought in the area. Instead of water from the lake being relatively near to the road for good wildlife viewing, it was more than a half a mile away. The beginning of March is supposed to be the rainy season in this part of Tanzania, which is why the tour companies consider it to be the low season and also why Martin and I had most of the parks and accommodations to ourselves. We did not see a drop of rain during our first three weeks of the trip. While a lack of rain might be a benefit for tourists on holiday, it can be disastrous for farmers in Tanzania who work fields that are not irrigated. Without rain, they cannot grow crops to feed their families and to earn money to live. That is one reason that the predicted droughts due climate change could have such devastating effects on this part of the world.

Instead of staying at Lake Manyara, we went to Tarangire and stayed at the Naitola Camp for three nights, which was very pleasant once we got there. On the way in, we drove through acacia scrub for about thirty minutes before someone from the camp came and found us. For many of these places, there not only were no signs to tell you which roads to be on, but there were no roads. I am amazed we did not get lost more often. There was no electricity at the camp, but we did fine without it. Because we were at a lower elevation, the temperature was much warmer than at Ngorongoro. On the 8th, we birded around the camp. On the 9th, we drove to a nearby river in the hope of seeing elephants coming in to drink. When we arrived, we found the riverbed was dry, but there was fresh elephant dung. During the entire trip, we saw a lot of dry riverbeds. Later that day, we went to an overlook to watch the sunset. Then we went for our only night drive of the trip. We spent the 10th exploring Tarangire National Park, including the Silale Swamp. The park is approximately 2,600 square kilometers within an ecosystem of more than 20,000 square kilometers on the Maasai steppes. It is the best park in Africa for elephants, with a population of more than 3,000.

Naitola Camp - Photo by William Young

Naitola Camp - Photo by William Young Tarangire National Park Sign - Photo by William Young

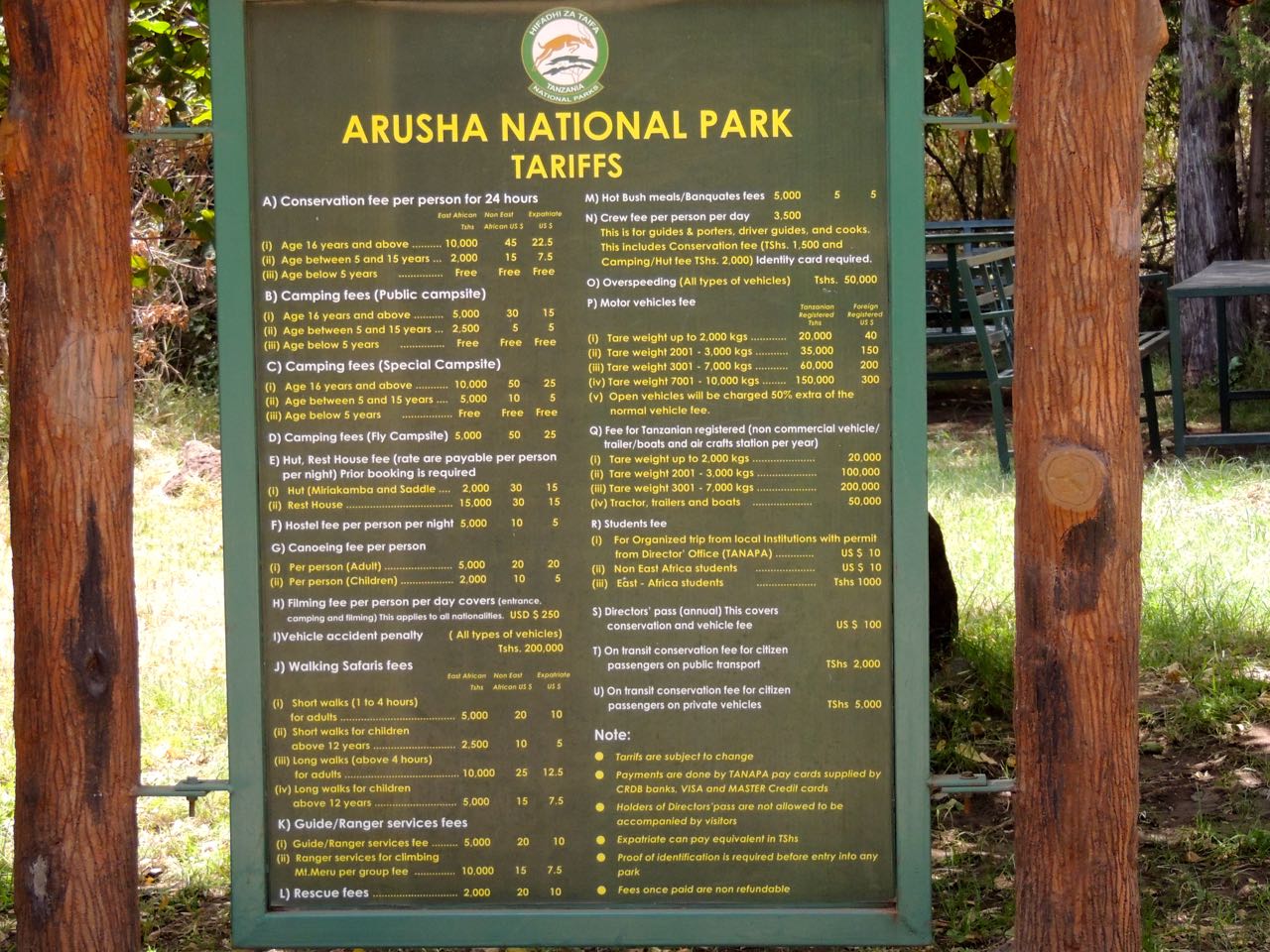

Tarangire National Park Sign - Photo by William YoungWe spent the evening of the 10th at the Karibu Heritage House in Arusha. "Karibu" is the Swahili word for welcome. On the 11th, we drove to a desert area to see the rare endemic Beesley's Lark. From this area, we had clear views of both Mount Kilimanjaro and Mount Meru. We had lunch with Simon King, an Australian who lives in Arusha and runs the tour company that set up our trip. We ate on the veranda next to his garden. We then drove to Arusha National Park, which lies between the peaks of Mount Kilimanjaro and Mount Meru. Most of Mount Meru, which is almost 15,000 feet high, is inside the park. The summit of Mount Meru is called Socialist Peak, a name given after the transition from colonialism to independence under Julius Nyerere. It is Tanzania's second highest mountain. Arusha National Park has many habitats, including a string of crater lakes, highland montane forest, and the summit of Mt. Meru. The park has only 337 square kilometers and derives its name from the Warusha tribe who live on the slopes of Mt Meru. We went to the Mikindu Observation Point, which overlooks fields where animals sometimes congregate. We stayed at the Momela campsite, which is in an area called Gongongare. While there, we saw our first fireflies of the trip. A guide named Mutobha from the park came and slept in our camp. He carried his AK-47 with him at all times. He knew a lot about birds, and on the 12th, he took us for a walk in an area near the camp. We spent the afternoon driving around the area near our campsite. On the 13th, we did more exploring around Arusha, going to a vista where we could see all of the lakes.

Beesley's Lark Conservation Area - Photo by William Young

Beesley's Lark Conservation Area - Photo by William Young Mount Kilimanjaro - Photo by William Young

Mount Kilimanjaro - Photo by William Young Arusha National Park - Photo by William Young

Arusha National Park - Photo by William Young Mount Meru - Photo by William Young

Mount Meru - Photo by William Young Mikindu Observation Point - Photo by William Young

Mikindu Observation Point - Photo by William Young Gongongare - Photo by William Young

Gongongare - Photo by William Young Momela Campsite - Photo by William Young

Momela Campsite - Photo by William Young Momela Overlook - Photo by William Young

Momela Overlook - Photo by William YoungWe then headed toward Mkomazi, which is Tanzania's newest and largest park. It is located in a stretch of land behind the Pare and Usambara Mountains. Mkomazi is connected to the Tsavo National Park of Kenya. The trans-border national park is the largest of its type in the world, with more than 26,000 square kilometers. It had taller grass than some of the other parks we had visited because there was not as severe a problem with overgrazing. It used to be a hunting reserve, and the animals there are still wary of humans from the hunting days. Once when we were in the park, we saw a Maasai boy running away when he saw us. He was not legally supposed to be there. We drove through Moshi, which was one of the most prosperous towns we saw. We then drove through Mwanga and reached Same (pronounced Sam-ay), where we stayed at the Elephant Motel for an evening. I was able to shower for the first time in a few days and clean numerous layers of dirt from my body. I was also able to wash a lot of dirt from my clothing. On the 14th, we went to the Dindira camp site where we stayed for two evenings. We were a short drive from elevated areas that allowed a good view of the lake and its surroundings.

Pare Mountains - Photo by William Young

Pare Mountains - Photo by William Young Elephant Motel - Photo by William Young

Elephant Motel - Photo by William Young Dindira - Photo by William Young

Dindira - Photo by William Young Dindira Campsite - Photo by William Young

Dindira Campsite - Photo by William YoungOn the 16th, we headed for the Amani Nature Reserve and stayed at the Amani Guesthouse for the following three evenings. Amani was different from all of the other places we had visited. A lot of natural history research is done there. In addition to the researchers in the area, there are about 20 villages, each of which has about 2,000-3,000 people. The area was like a large town or small city. A lot of people on motorbikes zoomed through. The nature reserve is part of the Eastern Arc Mountains, a group of biodiversity hotspots stretching from the Taita Hills in Kenya to the Udzungwa National Park in Tanzania, noted for their high number of endemic species. The habitat has rain forest, and there were a lot of tall trees, unlike the shorter trees we had encountered on our journey to this point. The rain forests are more than 30 million years old and have been evolving in isolation from the West African tropical forest for at least 10 million years. The Amani forests are particularly important because they are close to the Indian Ocean, have high humidity all year, and receive more than 10 centimeters (4 inches) of rain each month. During our stay at Amani, we used a local guide named Martin, who was quite good at finding birds. The area was settled in the late 19th century by German immigrants, and a lot of the area outside the Amani Forest Reserve is dedicated to tea production, terraced on the steep slopes of the mountain ranges. One afternoon, we took a walk in the rain forest. We did not see many birds, but being in a rain forest was exciting. This rain forest seemed a little different from some of the ones I have walked through in Australia and the American tropics, because there were more open areas. It was also good to be hiking after so many days of being jostled in the Range Rover.

Amani Tea - Photo by William Young

Amani Tea - Photo by William Young Amani Shopping Centre - Photo by William Young

Amani Shopping Centre - Photo by William YoungAt Amani, we met a couple named Tony (from Sweden) and Iskra (from Bulgaria) who were in the midst of a seven-month tour around Africa. On March 19, we gave them a lift into the nearby town of Muheza and continued on through the towns of Mkata, Kmange, and Lugoba before eventually reaching Morogoro. We stayed at the Arc Motel, which provided a bit of a respite from the camping. We could take hot showers, and there was electricity and Wi-Fi in the rooms. I heard loud chirping from a large House Sparrow roost outside my room. Before dawn, there was a loud chorus of frogs.

March 20 was probably the worst day of the trip. We tried to go to the Uluguru Nature Reserve. We had to drive for more than two hours on some of the worst roads we encountered on the trip. The reserve has rare endemic bird species such as Mrs. Moreau's Warbler. It is also called Winifred's Warbler by those who were on more familiar terms with Mrs. M. Mr. Moreau was a British civil servant who lived in the area in the 1930's, and he named the bird after his wife. The couple had a daughter they named Prinia, which is another nondescript little bird found in the area. We never reached the reserve. We experienced the first real rain of our trip, and when we were within ten kilometers of the entrance, we encountered a stretch of road that had been recently worked on, and it was a quagmire. Our vehicle became stuck in the mud, and with the help of some local people, we managed to get out of the mud and turned around so that we could go back to the motel. It was a market day, so while on our drive up and down the mountain, we saw people, mostly men, walking with 40+ pound stalks of bananas balanced on their head. I don't think there was a five-minute stretch when we did not pass people. In one stretch, we passed a school that appeared to be teaching young girls, many of them wearing a head scarf, how to hoe. At times, the rain was so heavy that streams of muddy water were running along the side of the road. A lot of men were trying to negotiate the difficult roads on motorbikes. Considering how difficult it was to reach our destination, Martin said that it might be in the Guinness Book of World Records as the least visited nature reserve in the world. Bernard said that we probably would have made it had it not been for the rain. We left our hotel right after breakfast, and being on such bad roads shortly after eating a big meal really upset my stomach. I felt as if I was in a low-speed blender for more than six hours. But once we got back to the hotel and I had a chance to lie down for a bit, I felt fine.

We left for Udzungwa on March 21. Udzungwa Forest National Park is the largest and most biodiverse of a chain of a dozen large forested mountains rising from the flat coastal scrub of eastern Tanzania. The mountains are known collectively as the Eastern Arc Mountains. This area is known for its endemic plants and animals. Udzungwa is the only one of the ancient ranges of the Eastern Arc that has been accorded national park status. It is also unique within Tanzania in that its closed-canopy forest spans altitudes of 250 meters (820 feet) to above 2,000 meters (6,560 feet) without interruption. We stayed for four nights at a campsite called Hondo Hondo, which means "hornbill".

Udzungwa Forest National Park - Photo by William Young

Udzungwa Forest National Park - Photo by William Young Hondo Hondo Campsite - Photo by William Young

Hondo Hondo Campsite - Photo by William YoungOn the 22nd, we explored some of the steep rain forest trails in the park. A young guide led us into foliage that was so dense that we could not see much. It was a bit like a Marines basic training hike, with the added features of biting ants and thorny plants.

On the 23rd, we drove to Kilombero, which was about 90 minutes from the Hondo Hondo camp. It was one of the liveliest villages/towns we encountered on our trip. We hired a boat and took a ride on the Kilombero River. On the 24th, we drove to another part of Udzungwa in the rain. Many of the paths we wanted to walk on had ankle-deep water from the rains the previous evening, so we were unable to get through. In the afternoon, we walked through some of the agricultural fields near our campsite. We had to cut this walk short because of a rainstorm that we could see coming toward us.

Road to Kilombero - Photo by William Young

Road to Kilombero - Photo by William Young Road to Kilombero - Photo by William Young

Road to Kilombero - Photo by William Young Road to Kilombero - Photo by William Young

Road to Kilombero - Photo by William Young Road to Kilombero - Photo by William Young

Road to Kilombero - Photo by William Young Road to Kilombero - Photo by William Young

Road to Kilombero - Photo by William Young Kilombero - Photo by William Young

Kilombero - Photo by William YoungOn the 25th, we decided that instead of trying to go to some of the areas in Udzungwa that we could not reach the day before, we would drive to nearby Mikumi National Park. Mikumi was like the parks we had visited before reaching Amani. It has vast expanses of open plains, and there were a lot of mammals walking around. We were able to get in a full afternoon at Mikumi and all of the next morning. We stayed for two nights at the Angalia Tented Camp, which is run by the Maasai. The camp was very comfortable, and the food was some of the best we had on the trip. On the afternoon of the 26th, we walked in an area near the campsite, guided by one of the Maasai. On our last morning in Tanzania, we had to drive on the highway that went through Mikumi National Park. We saw elephants, giraffes, impalas, warthogs, and Cape Buffalos. There was a Marabou and a bunch of White Storks. At one point, we had to stop to let Southern Ground-Hornbill cross the road. It seemed strange to routinely see these creatures while we were riding in a car without being on a wildlife expedition.

Road to Mikumi - Photo by William Young

Road to Mikumi - Photo by William Young Mikumi - Photo by William Young

Mikumi - Photo by William YoungThe Angalia Tented Camp is about a 5 1/2 hour drive from the Dar es Salaam airport unless one runs into traffic problems. My flight was at 4:40, and we left at 8 am. We were doing fine until we were about 20 minutes from the airport, and traffic simply stopped for two hours at an intersection ahead of us. When we eventually reached the intersection, we saw no apparent reason for the stop. I ended up making my flight by about 15 minutes.

Angalia Tented Camp - Photo by William Young

Angalia Tented Camp - Photo by William YoungI was very pleased with the itinerary set up by East African Safaris, but I might make a few changes. I would definitely cut out the trip to Uluguru, where we got stuck in the mud. Even if we had reached the reserve, we probably would not have seen much, both because of the rain and arriving in late morning when bird activity tends to slow down. I would probably cut a couple of the four nights we were in Udzungwa, keeping the Kilombero leg and some of the birding around the camp and the entrance to the park. The two evenings at Udzungwa and the day at Uluguru probably could have been better spent up north, with an extra day at Serengeti, Tarangire, and Ngorongoro. And I think the trip could have been more pleasant had we avoided Dar es Salaam and had flown in and out of Arusha. Dar es Salaam is a large city that is in many ways dysfunctional, and I do not think we would have missed much in the way of wildlife had we avoided it altogether.

BIRDSWe encountered roughly 455 species of birds from 79 families. Altogether, we estimate that we encountered more than 34,000 individual birds.

OstrichOstriches were relatively common during the beginning of our safari. We saw them in seven of the first ten days, with numbers ranging from a dozen to 40. They generally were in small to medium-sized groups on the plains. Because they are so tall, Ostriches can be seen from a considerable distance. They can run quickly. We also saw males and females performing sexual displays, which involve a lot of feather fluffing. Ostriches look much larger than the Emus I saw in Australia. The cassowaries I saw in Australia had small vestigial wings, but the vestigial wings on the Ostriches were quite long. The males have long pink necks, while the female necks are grayer. Some young have bodies that are tan rather than black or brown like the adults. Ostriches sometimes sit on the ground with their legs beneath them as if incubating eggs. When standing, they sometimes reach their long neck down to peck at something on the ground, which might be what gave rise to the myth about them putting their head in the sand.

Ostrich - Photo by William Young

Ostrich - Photo by William Young Ostriches - Photo by William Young

Ostriches - Photo by William Young Ostrich - Photo by William Young

Ostrich - Photo by William Young Ostrich - Photo by William Young

Ostrich - Photo by William Young Young Ostrich - Photo by William Young

Young Ostrich - Photo by William Young

GrebesWe saw Little Grebes on only four days. We saw one at Ngorongoro and six at Tarangire. When we got to the lakes around Arusha, we saw hundreds each day. A lot of them were swimming relatively close to the shore so that the little yellow spot near the bill could be seen. It was sometimes difficult to photograph them because they dove so frequently. We saw both breeding and the slightly duller non-breeding birds. In flight, they show white under their wings.

Little Grebe - Photo by William Young

Little Grebe - Photo by William Young

CormorantsThe Long-tailed Cormorant was far more common than the Great. We saw a couple thousand Long-tailed on the boat trip around Lake Victoria. They are about half the size of the Great. The immatures have a lot of white below. We encountered them in only three places other than Lake Victoria, and in each case, only one. We saw one at Kilombero near the end of the trip as well as at Ngorongoro and Lake Manyara. We saw only three Great Cormorants. One was on our trip along the coast around Dar es Salaam, and the other two we viewed at a considerable distance from a hill in Arusha.

Long-tailed Cormorant - Photo by William Young

Long-tailed Cormorant - Photo by William Young

Herons, Egrets, and BitternsWe saw more than 2,200 Cattle Egrets on 11 days. They were in fields as we drove through agricultural areas as well as in Dar es Salaam. Some were in breeding plumage, showing considerable yellow-orange feathering, especially the ones we saw in Kilombero. At Ngorongoro, there were enormous flocks of Cattle Egrets flying above some of the mammals. We also saw a considerable number at Lake Manyara, and some stood on the backs of hippopotami. We saw Black-headed Herons on 14 days, and we saw about 225 in total. We were able to get close to some. They are about the same size and shape as Grey Herons, but they have a black head and neck. Their underwings have light coverts and a broad black trailing edge, while the Grey Heron's underwings are solid grey. We saw Grey Herons on 9 days, with a total of 34 birds. They look like pale Great Blue Herons, but the markings on their plumage stand out more. Little Egrets were fairly common. We saw 30 along the coast in Dar es Salaam, 35 at Lake Manyara, and about 150 around Lake Victoria. We saw between two and five on four other days. They resemble Snowy Egrets, who are not present in Tanzania. We saw good numbers of Squacco Herons on numerous days. They are light brown and streaked, shaped like a night-heron. The white on their wings can be seen when the bird is standing, but it is more apparent when the bird flies. Squacco Herons were especially common at Kilombero (50) and Lake Manyara (25). They tended to be near the edge of the water or next to reeds where they were well camouflaged.

Cattle Egret - Photo by William Young

Cattle Egret - Photo by William Young Cattle Egrets - Photo by William Young

Cattle Egrets - Photo by William Young Cattle Egrets over Ngorongoro Crater - Photo by William Young

Cattle Egrets over Ngorongoro Crater - Photo by William Young Black-headed Heron - Photo by William Young

Black-headed Heron - Photo by William Young Grey Heron - Photo by William Young

Grey Heron - Photo by William Young Little Egret, Long-toed Lapwing, and Squacco Heron - Photo by William Young

Little Egret, Long-toed Lapwing, and Squacco Heron - Photo by William YoungWe encountered seven other heron species on a few days or less. At Kilombero, we saw a flying Purple Heron, who has bluish-purple wings and a brown body. We did not see the much larger Goliath Heron, whose plumage is similar. We saw one Striated Heron at Lake Victoria, who looks like a grayish version of a Green Heron. Around Ngorongoro, we found a tree containing 20 Black-crowned Night-Herons, the only ones we saw on the trip. In Dar es Salaam, we saw a dark phase Dimorphic Egret, who has a little white mark at the front of each wing in flight. We saw Great Egrets at Lake Victoria and Mkomazi. We saw a dozen Black Herons in a pond at Manyara and another one during our day in Dar es Salaam. And we saw a total of 17 Intermediate Egrets on three different days. We saw 10 at Tarangire. They have slightly shorter necks than Great Egrets, and their gape line stops below the eye instead of extending past it.

Intermediate Egret - Photo by William Young

Intermediate Egret - Photo by William Young

HamerkopA Hamerkop, whose name comes from an Afrikaans word for hammer head, surprised us on our first day in the Serengeti by being in water right next to the road, about 15 feet from where our vehicle stopped. It was so preoccupied with hunting that it did not seem to notice us. It is a solid brown bird that looks like a heron with a hammer head. At Mikumi, we saw one on the road ahead of us, hammering a frog with its bill. Near the water at Mkomazi, we saw a Hamerkop nest, which is a gigantic ball of sticks that appeared to have a diameter of five or six feet. When they are flying at a distance, Hamerkops have clearly defined wing strokes and look a bit like Aquilla eagles. We saw about 23 of them on eight days.

Hamerkop - Photo by William Young

Hamerkop - Photo by William Young Hamerkop Nest - Photo by William Young

Hamerkop Nest - Photo by William Young

StorksThe storks in Tanzania often congregate in groups, and they freely mix with other species. They are large and easy to see, and we saw an estimated 4,500 storks of six species. About two thirds were Abdim's Storks, and almost all of these were seen on the day we visited Ngorongoro. They seemed to be everywhere we looked while we were in the crater. Their feathers have a purple iridescent sheen. The belly is white, and some of the white shows near the upper edge of the wing when the bird is walking around. They have blue facial skin below the eye, and they have an eyering, the front half of which is red and the back half tan. The ankle joints are red, and they have white feathering on the top of their legs.

Abdim's Stork - Photo by William Young

Abdim's Stork - Photo by William YoungOne of my favorite birds of the trip was the Marabou Stork, whose unbelievable ugliness makes it endearing. I saw more than 600 Marabous on 12 days in many different circumstances. On Lake Victoria, we stopped at a market run by the Sukuma Tribe, who are fishing people. Among the people busily conducting business at the market were about 50 Marabous, who were taller than most of the children and as tall as some of the adults. They walked through the market area as if they were customers, and the people did not seem to pay much attention to them. At the Rhino Lodge near Ngorongoro, Marabous walked on the front lawn and stood on the chimneys of some buildings. I found a couple of Marabou flight feathers on one of the lawns, and they are 22 inches long. One Marabou who was standing in front of me spread its wings and showed its huge wingspan. The wings are very broad, making a whooshing sound in flight. I tried to give one the Richard Avedon treatment by photographing it in different light and from different angles, but nothing could make it look attractive. Marabous sometimes soar like vultures, and they eat carrion like vultures. We saw them at a zebra kill at Ndutu, eating the remains with the vultures. Some of the vultures are very large, but the Marabous look much larger, and with their long legs, tower over the vultures. Sometimes we saw Marabous pecking at or standing on piles of garbage. At the Rhino Lodge, one of the Marabous found what looked like a small sandwich in a sealed cellophane packet. The Marabou very proficiently shook the packet to open it and get the sandwich out, showing that it knew not to eat the cellophane. At Mikumi, we saw a single one in a field eating something that had died. Marabous look like old men wearing a dirty dark gray jacket with a dirty white fir collar. Their heads are not bald, but have some gnarled hairlike fuzz on top. The neck is pink, and the head is a somewhat darker shade of the same tone. They have large eyes, and their forehead makes them look as if they had just dipped their head into tar. The skin on the neck is wrinkled rather than smooth (which is why they look old), and the texture of the bill is rough rather than smooth — it looks as if it is made from a piece of wood that has not been sanded. The ear holes are slightly below eye level and fairly prominent. At the base of the neck is a large blood-red patch of bare skin; when the bird preens its belly feathers, the spot is clearly visible.

Marabou Stork - Photo by William Young

Marabou Stork - Photo by William Young Marabou Stork - Photo by William Young

Marabou Stork - Photo by William Young Marabou Stork - Photo by William Young

Marabou Stork - Photo by William Young Marabou Stork - Photo by William Young

Marabou Stork - Photo by William Young Marabou Stork and Little Egrets at Sukuma Market - Photo by William Young

Marabou Stork and Little Egrets at Sukuma Market - Photo by William Young Marabou Stork Wingspan - Photo by William Young

Marabou Stork Wingspan - Photo by William Young Marabou Stork - Photo by William Young

Marabou Stork - Photo by William Young Marabou Stork Foot - Photo by William Young

Marabou Stork Foot - Photo by William YoungEuropean White Storks were common, and we saw about 600. About 500 were in the Serengeti, where they were scattered all over. We also had nice views of them the next day at Ndutu, where some perched on downed branches next to the water. They have a bright red bill and red legs. Their plumage is almost all white except for the broad black trailing edge of their wings. We saw an estimated 260 of the similar Yellow-billed Storks on four days. They have mostly white plumage, a broad black trailing edge to the wings, and red legs like the European White Stork. But the Yellow-billed Stork has a yellow bill with bare red skin on its face and forehead. Its tail is black, and when I saw one of the birds stretch a wing at the Momela camp, I could see a pinkish tinge to the feathering. The pastel feathering makes the Yellow-billed seem more attractive than the hygienic white of the European White.

European White Storks - Photo by William Young

European White Storks - Photo by William Young European White Stork and Wildebeests - Photo by William Young

European White Stork and Wildebeests - Photo by William Young Yellow-billed Stork - Photo by William Young

Yellow-billed Stork - Photo by William YoungIn addition to the Abdim's, we saw two other dark stork species. The African Openbill is a uniformly dark bird, except for the bill which looks as if it is warped or damaged. From certain angles, you can see light shine through it. We saw about 30, with most of them at Tarangire. The Woolly-necked Stork has solid dark wings, but it has a white head, neck, and belly. Its forehead and face are also dark. We did not see any until we got to Dindira Swamp about midway through the trip. We saw 15 there, and we also saw some at a nearby scenic overlook. I photographed one near a large stick nest in a tree near the overlook. Red-billed Buffalo-Weavers were buzzing around the nest, and it appeared that they might have built their nests under the stork nest.

Yellow-billed, Marabou, and African Open-billed Storks - Photo by William Young

Yellow-billed, Marabou, and African Open-billed Storks - Photo by William Young Woolly-necked Stork - Photo by William Young

Woolly-necked Stork - Photo by William Young Woolly-necked Stork - Photo by William Young

Woolly-necked Stork - Photo by William Young Woolly-necked Stork at Nest - Photo by William Young

Woolly-necked Stork at Nest - Photo by William YoungOne of the most beautiful birds of the trip, to balance the ugliness of the Marabou Storks, was the Saddle-billed Stork. We saw only four during the trip. One was at Dindira with the Woolly-necked Storks and a few European White Storks. We had much better views at Mikumi, where two were not far from our vehicle. Saddle-billed Storks are almost as big as Marabous, but they do not seem as bulky. They have a black head and neck, and the rest of the body is black-and-white, including their upperwings and their underwings. At Dindira, on one who was taking off, and I could see the black-and-white pattern under the wing. The breast is white with a small blood red spot of bare skin in the middle. The bill is red at the base and at the front half. There is a large saddle of yellow skin on top of the base that extends a bit into the black, and they also have two small yellow wattles that hang below the base of the bill and can be difficult to see. The Mikumi pair was a male and a female, with the female having an orange eye and the male a dark eye.

Saddle-billed Stork Female - Photo by William Young

Saddle-billed Stork Female - Photo by William Young Saddle-billed Stork Male - Photo by William Young

Saddle-billed Stork Male - Photo by William Young

Ibises and SpoonbillIbises were fairly common during the trip. I saw a flyover Sacred Ibis when I was in the airport in Addis Ababa, and we saw some feeding during our day in Dar es Salaam. They look distinctive when flying, appearing almost all white with a black head and neck. We did not see large flocks, but they were not scarce. We saw 80 on ten days. We saw about half as many Hadada Ibis, who are uniformly dark. At Serenity by Lake Victoria, we heard the loud three- or four-note call of the Hadadas. They have a thicker bill than the Glossy, and there is a bit of red on the upper mandible. I had close views of some who were on the roof at the Karibu Heritage House. We saw roughly as many Glossy as Hadada. The Glossy is likewise all dark, but it is much more delicate looking. It has a more slender bill that has no red on it. We saw a lot of them at Lake Manyara near the Hippo Pool. I saw a few African Spoonbills, who are all white with a yellow bill and red legs. Two at Dindira had bare red skin at the base of the bill.

Hadada Ibis - Photo by William Young

Hadada Ibis - Photo by William Young African Spoonbill - Photo by William Young

African Spoonbill - Photo by William Young African Spoonbills - Photo by William Young

African Spoonbills - Photo by William Young

FlamingosMost of the Flamingos we saw were in Momela Lake. There were about a thousand Greater Flamingos and 5,000 Lesser Flamingos. The Lessers are smaller and pinker, and they have a solid dark bill rather than a black-tipped light bill like the Greater. We saw large mixed flocks, and sometimes we could see the Greaters standing taller in the crowd. In flight, the flamingos had pink underwings. Sometimes, they floated on the water like swans. They spend a lot of time bent over with their bills in the water. On our day in Dar es Salaam, we drove past a flock of about 15 Lessers. And we saw a distant flock of about 200 Greaters at Ndutu. We did not see flamingos often, but when we did, we tended to see a lot of them.

Greater Flamingos - Photo by William Young

Greater Flamingos - Photo by William Young Lesser Flamingos - Photo by William Young

Lesser Flamingos - Photo by William Young

Geese and DucksThe waterfowl in Tanzania were somewhat of a disappointment. We saw ten species, but we tended not to see them often, even in waterholes and other bodies of water. We saw more than 100 Egyptian Geese on 9 days, and they were fairly common. At Ndutu, we saw one with goslings. Egyptian Geese are large and tan, with black around the eye, a pinkish bill, and white on the face. They do not look attractive. Nor do the much larger Spur-winged Geese, who are black and white, with bare red skin on the face making them look like supersized Muscovy Ducks. The Comb Duck also has black and white plumage, but it has a dark bill with a large knobby protrusion on the upper mandible — a bit like the knobby protrusion on the lower mandible of the Musk Duck in Australia. We saw four at Tarangire, but because they were sleeping, I could not see their bills well. I had a close look at a young one at Dindira, who had a dirty brown head rather than a dirty white head like the adults. Some of the smaller ducks were not all that attractive either. We saw 10 African Black Ducks at Silale Swamp at Tarangire, and they looked rattier than American or Australian Black Ducks. We saw Hottentot Teals, who are small and have a light cheek, and they too look plain and dirty. In Arusha, we saw Maccoa Ducks, who are in the same genus as the Ruddy Duck. The bill looks more gray than blue, and the plumage appeared to be a washed-out brown. We saw them on two days in the same place, but we saw more and had better looks the second day.

Egyptian Geese and Lesser Flamingos - Photo by William Young

Egyptian Geese and Lesser Flamingos - Photo by William Young Spur-winged Goose - Photo by William Young

Spur-winged Goose - Photo by William Young Comb Duck - Photo by William Young

Comb Duck - Photo by William Young Maccoa Duck - Photo by William Young

Maccoa Duck - Photo by William YoungNot all the ducks were dingy. At Dindira Swamp, we saw about a hundred White-faced Whistling-Ducks, who are handsome. They make a distinctive three- or four-note whistling call. Their bodies look gray, with a brown neck and a whitish face. The head looks triangular. Six Red-billed Ducks swam around Dindira, and in the right light, they are quite beautiful, with their brown body, white cheek, and bright red bill. We had seen larger groups of them at Ndutu and Ngorongoro, but we had better views at Dindira. Cape Teal have a limited palette to work with, but their pinkish-red bill, if seen in good light, makes them look handsome. They are small and have a greyish-brown body. We had our best looks at them at the lakes around Arusha. A surprise was seeing a pair of Northern Shovelers at Ngorongoro, not far from where we saw a rhinoceros.

White-faced Whistling-Duck - Photo by William Young

White-faced Whistling-Duck - Photo by William Young White-faced Whistling-Ducks - Photo by William Young

White-faced Whistling-Ducks - Photo by William Young White-faced Whistling-Duck and Comb Duck - Photo by William Young

White-faced Whistling-Duck and Comb Duck - Photo by William Young Red-billed Ducks - Photo by William Young

Red-billed Ducks - Photo by William Young Cape Teal - Photo by William Young

Cape Teal - Photo by William Young

SecretarybirdSecretarybirds are big, tall, and have a lot of character. They appear to be wearing black leggings as they stomp around. They mostly stay on the ground. Their wings are long and broad, and they resemble some of the larger herons or storks when they fly. One stood next to a Black-headed Heron, who looked tiny in comparison. They have black feathers sticking out of the back of their head, and we saw one walking around in a crazed manner with these feathers erect. One explanation of the name is that the black feathers are like the pens carried by secretaries. We also saw one who appeared to be going after some prey — the scientific species name is serpentarius, and they kill a lot of snakes by stomping on them.

Secretarybird - Photo by William Young

Secretarybird - Photo by William Young Secretarybird - Photo by William Young

Secretarybird - Photo by William Young Secretarybird and Black-headed Heron - Photo by William Young

Secretarybird and Black-headed Heron - Photo by William Young

OspreyWe saw one Osprey perched in a distant tree at Mikumi. The bird later flew in our direction, allowing a closer look.

Hawks, Eagles, and KitesWe saw about 45 species of raptors (counting falcons, Osprey, and Secretarybird). The most common was the Black Kite. It has long wings and a slightly forked tail. If you see one at close range, there are different shades of dark feathers in the plumage, but from a distance, the bird can appear all dark. At our lunch site at Ngorongoro, Bernard warned us to protect our food, because Black Kites swoop down and try to steal food when you are not looking. I saw this species in Australia, which has no species of vultures, and Black Kites fill the scavenger niche. I saw them on ten days, including in Addis Ababa, but we saw most of the 530 on the drive from the airport in Mwanza to our accommodations at Serenity. The Common Black-shouldered Kite was fairly common. We saw them on seven days, but only singles or pairs. It is basically the same bird as the White-tailed Kite in North America and the Australian Kite. It is a sleek white-and-gray kite with some black on the wings, and it sometimes hovers like a kestrel. Martin saw a Bat Hawk at Serenity whom I did not see.

Common Black-shouldered Kite - Photo by William Young

Common Black-shouldered Kite - Photo by William Young Common Black-shouldered Kite - Photo by William Young

Common Black-shouldered Kite - Photo by William YoungThe African Fish-Eagle is beautiful and reminded me of the Brahminy Kite (who is in the same genus) in Australia. It is a stocky black-and-chestnut bird with a white head, neck, breast, and tail. We saw single birds on five days, and occasionally we would hear their loud piercing call.

Some of the vultures in Africa are huge. The Rüppell's Griffon and African White-backed Vulture are both about 40 inches, with the Rüppell's being slightly larger. The adult Ruppell's has white edging to the feathers on its back, which the White-backed does not, which is confusing. The adult Ruppell's bill is light on the front half, while the bill of the adult White-backed is all dark. Immature Rüppell's have an all dark bill. In flight, the immatures of the two species are difficult to tell apart, but the adults are slightly different, because the White-backed has more white on its underwing coverts. As with all the large vultures, they have broad wings for soaring and a short tail. On the ground, they move by taking fast hops, which is endearing when done by a songbird, but comical when done by a huge vulture. We saw an estimated 58 White-backed and 47 Rüppell's, and we saw the White-backed on twice as many days. Lappet-faced Vultures are the largest vulture in Tanzania. They often dictate what vultures and other scavenging creatures can do at a kill site, because they are the birds most capable of ripping open flesh. They are almost entirely black, with white leggings. The head is featherless, mostly red-and-blue, and the front half of the bill is light colored. The species name comes from the fold of pink skin (a lappet) hanging from its neck. When they soar, they have a diagnostic small patch of white at the bottom of the belly. At a zebra kill at Ndutu, I saw a couple of them standing about 50 yards from where the other vultures and Marabou Storks were eating, and they looked as if they were kissing. I also saw three of the smaller vultures. The most common vulture on our trip was the Palm-nut Vulture. We saw two on our day in Dar es Salaam, showing distinctive black-and-white underwings. One was perched at Dindira, and we could see the bare red skin around the eye. The bill is large. The following day, we saw a perched immature, who is mostly brown. We saw 16 on eight days, mostly singles or pairs. I saw only a couple of White-headed Vultures, and one was in Addis Ababa. We also saw one in the Serengeti, and its head looked pinkish. The bird is mostly black, with white on the belly and some on the underwing. We saw our first Egyptian Vulture while waiting outside the park at Lake Manyara. It has a white body and white underwing coverts. We saw an immature at Tarangire whose plumage looked buffy.

Rüppell's Griffon Vultures and Marabou Stork - Photo by William Young

Rüppell's Griffon Vultures and Marabou Stork - Photo by William Young Rüppell's Griffon Vultures and Marabou Storks at a Zebra Kill - Photo by William Young

Rüppell's Griffon Vultures and Marabou Storks at a Zebra Kill - Photo by William Young Lappet-faced Vultures - Photo by William Young

Lappet-faced Vultures - Photo by William Young Lappet-faced Vultures - Photo by William Young

Lappet-faced Vultures - Photo by William YoungBataleurs were fairly common. The adult male's body is stocky, looking like a black-and-gray parrot with some brown on the back. The bill is bright red. In flight, the underwings are almost all white, and the very short tail is red, which is a striking combination with the black body. We saw 28 on 12 days. We saw a pair at relatively close range in a tree at Dindira with an immature Black-breasted Snake-Eagle. The first Black-breasted Snake-Eagle I saw was on the first day in the Serengeti. It was fairly large, with a dark breast that cleanly ended in a straight line next to a white belly. The immature is brown on the back and white below. I saw single birds on four different days. The Stevenson field guide calls this species the Black-chested Snake-Eagle. In the same genus is the Brown Snake-Eagle, who is solid chocolate brown. Like the Black-breasted, it has intense yellow eyes. We had a good view of one perched in a Baobab tree near our camp at Naitola. At Amani, we saw a Southern-banded Snake-Eagle on two different days — probably the same bird. It appeared to be an immature, and it was slightly smaller than the other two snake-eagle species we saw. It was gray on the back, and the underparts were rufous with irregular narrow white bands.

Black-breasted Snake-Eagle Immature (above) and Bataleurs - Photo by William Young

Black-breasted Snake-Eagle Immature (above) and Bataleurs - Photo by William Young Brown Snake-Eagle - Photo by William Young

Brown Snake-Eagle - Photo by William YoungWe saw a lot of harriers of four different species on the trip. Some are difficult to identify. The adult female and young of the Pallid and Montagu's Harriers have white rumps. The adult males of both these two species are gray, with the Pallid being lighter, and the Montagu's having a horizontal black mark on each upperwing in flight. The female Pallid is chocolate brown on the back and lighter brown below. The adult African Marsh-Harrier is also chocolate brown, with a little bit of white on the head. We observed one eating the remains of a roadkill Thomson's Gazelle. The adult Eurasian Marsh-Harrier was the only one of the four who had a buffy head. Sometimes, a lot of bird species in a wetland area would flush at the same time because one or more harriers were cruising around. Combined, we saw 77 of the four species, ranging from 11 Europeans to 32 Montagu's. We also saw African Harrier-Hawks, who are not closely related to the harriers. The first one I saw was near our campsite at Momela, and I identified it immediately from the distinctive barred underwings with a thick black trailing edge. The bird perched in a nearby tree where we could see the yellow skin around the eye and the black spots on its mostly gray body. At Udzungwa, we saw a young harrier-hawk who did not have as pronounced an underwing pattern and was not nearly as easy to identify.

Pallid Harrier - Photo by William Young

Pallid Harrier - Photo by William Young African Marsh-Harrier - Photo by William Young

African Marsh-Harrier - Photo by William Young African Harrier-Hawk - Photo by William Young

African Harrier-Hawk - Photo by William YoungThe chanting-goshawks, Gabar Goshawk, and Lizard Buzzard all look similar. We had numerous good looks at Eastern Chanting-Goshawks at our Ndutu campsite, where they perched in the trees near our tents. They are gray above, have a gray-and-white barred belly, a yellow cere, and bright red legs. I could sometimes hear their loud chanting vocalization. We saw nine on six days. Gabar Goshawks are similar, but they have a red cere and are only a little more than half the size. We saw a perched melanistic Gabar at Ndutu, and it had white bars on its undertail; in its slightly open wings, I could see some white on the underwing. We had seen this bird fly, and it can move very quickly. At Amani, we found a perched Lizard Buzzard, who was very similar to the Gabar Goshawk, but had white on the throat. We had a difficult time seeing the vertical black line on the throat.

Eastern Chanting-Goshawk - Photo by William Young

Eastern Chanting-Goshawk - Photo by William Young Gabar Goshawk - Photo by William Young

Gabar Goshawk - Photo by William YoungWe saw only two accipiters and two buteos. We saw a Shikra, a small accipiter, in the Serengeti. And at Amani, we saw a Great (Black) Sparrowhawk, who is about twice as large. I could see the black marks on the flanks as it flew over. We saw a European Buzzard on three different days. The adult had a dark brown back and a reddish brown tail. Much more common were Augur Buzzards. The adults are distinctive, looking totally white below, except for a narrow black trailing edge to the wing and a short red tail. I had great looks at a perched one at our camp at Ndutu. We also saw a black phase bird, whose body and underwing coverts were black instead of white.

Augur Buzzard Adult - Photo by William Young

Augur Buzzard Adult - Photo by William Young Augur Buzzard Immature - Photo by William Young

Augur Buzzard Immature - Photo by William YoungWe saw many different species of eagles. Many Aquila eagles (the genus that contains the Golden Eagle) look alike and can be difficult to tell apart. We saw 13 Tawny Eagles on five days. They have uniformly dark underwings. The Steppe Eagle is a little darker and has a horizontal white line extending the length of the underwings. The Wahlberg's Eagle is smaller than the other two and is uniformly brown below. At Arusha, we saw a perched Lesser Spotted Eagle, who is plain brown with a trace of light spotting on the back. This bird was probably an immature, because it had a dark eye. On the way to Arusha, we saw a Verreaux's Eagle, who is the darkest of the Aquila eagles, with black plumage. We saw one flying, and it has white patches near the end of its wings. The much smaller Long-crested Eagle (not an Aquila) has similar dark plumage with white wing patches. We saw six on five days, including a couple perched ones. The first one was where we stopped for lunch at Serengeti National Park, and I could see the long crest flapping in the breeze. Very little white shows on perched birds. At Tarangire, we saw a perched adult African Hawk-Eagle, who had a dark back, black streaks on its white breast, and a black terminal tail band. In the Serengeti, we saw both a perched immature and a perched adult Martial Eagle. The adult has small dots rather than streaks on its breast. The immature's breast has no spots, but has a tinge of red. The only African Crowned Eagle we saw was a high soaring bird at Amani. It appeared to have more white near the tips of its wings than on the rest of the underwing.

Long-crested Eagle - Photo by William Young

Long-crested Eagle - Photo by William Young Martial Eagle - Photo by William Young

Martial Eagle - Photo by William Young

FalconsWe saw good numbers of three falcon species. African Pygmy-Falcons are only eight inches, with a light gray back, white underparts, rufous back, barred undertail, and red legs. We had good looks at a couple near the Ndutu campsite. We saw a tree at Mikumi with ten perched Amur Falcons. Later, we saw another tree with five. They did not appear to be very big, and when one flew, we could see the white underwing coverts on their black wings. Bernard speculated that these two groups of falcons were migrating and had stopped at Mikumi to rest. The greatest number of any falcon species we saw was an estimated 173 Lesser Kestrels seen on 9 days. We saw very large numbers the day we drove from Arusha to the Beasley's Lark area. During some stretches of road, there seemed to be one on every utility wire, and some wires had more than one. They have a long angular appearance, and the adult males have a plain back.

African Pygmy-Falcon - Photo by William Young

African Pygmy-Falcon - Photo by William YoungWe encountered seven other falcon species. I saw two Peregrines, and Martin saw another. We saw a perched Eurasian Hobby near the entrance at Mikumi on our last full day of birding. Later that morning, an Eleanora's Falcon zoomed by us. At Ndutu, we saw a Common Kestrel, who did not have a plain back like the Lesser. The day before in the Serengeti, we had prolonged looks at a cooperative Greater Kestrel, who has a light eye and a light brown body covered with little dark bars. We saw it pounce on prey and return to an area where we could watch it. On one of our drives to the Serengeti, we saw a perched Sooty Falcon, who looked sleek. We could see the dark outer half of its wings when it flew.

Greater Kestrel - Photo by William Young

Greater Kestrel - Photo by William Young Greater Kestrel - Photo by William Young

Greater Kestrel - Photo by William Young

Pheasants, Grouse, and AlliesIn the Serengeti, we saw a half dozen Coqui Francolins on the first day (including a female with three chicks by the side of the road) and a pair on the second. The adults are small and round with a lovely tan facial pattern. On one of our days near the Naitola campsite, we saw a pair of Crested Francolins. They also looked small and round, and they had a white supercilium. The Hildebrandt's Francolins looked much larger and are mottled below. We heard their calls, which the Stevenson field guide describes as: "...a wooden crescendo of rapid notes tunk-unk-unk-unk with the first loudest. May continue for long periods breaking into an insane bout of screaming, often given in duet." That is a fairly accurate account of what we heard. Tanzania's three species of spurfowls are in the same genus (Francolinus) as the francolins. The Grey-breasted Spurfowl is an endemic found only in a small area from Mwanza to the Serengeti. The three we saw in the Serengeti had a streaked gray breast and a red throat. We saw 46 Yellow-necked Spurfowl, with the most around the Naitola campsite and fewer around Mkomazi. They are handsome, with red skin around the eyes and a bare yellow throat. They have grayish legs and a similar colored bill. We did not see any Red-necked Spurfowl until the final full day of the trip at Mikumi. We saw ten, and some were close to our vehicle. Most of their bare parts are bright red — bill, skin around eyes, neck, and legs. The back is dark grayish-brown, and the underparts are black, streaked with gray. Two Common Quail flew near the entrance to Tarangire. They looked much smaller than the francolins. Helmeted Guineafowl were very common, and we saw 88 on nine days. Their huge black body with tiny speckles is much larger than a francolin's. They have blue skin on the neck, red skin on the face, and a horny casque.

Coqui Francolin Male and Female - Photo by William Young

Coqui Francolin Male and Female - Photo by William Young Crested Francolins - Photo by William Young

Crested Francolins - Photo by William Young Hildebrandt's Francolins - Photo by William Young

Hildebrandt's Francolins - Photo by William Young Yellow-necked Spurfowl - Photo by William Young

Yellow-necked Spurfowl - Photo by William Young Red-necked Spurfowl - Photo by William Young

Red-necked Spurfowl - Photo by William Young Helmeted Guineafowl - Photo by William Young

Helmeted Guineafowl - Photo by William Young Helmeted Guineafowl - Photo by William Young

Helmeted Guineafowl - Photo by William Young

CraneThe Grey Crowned Cranes were much more beautiful than they appear in the field guide. We saw some of these stunning birds glistening in the sunlight with their tight little bunch of feathers in the back of the head. They have a black crown and throat, a white cheek, a light eye, bare red skin near the ear, and a red wattle hanging from the chin. The neck is light gray and becomes a series of plumes that blend in with the darker gray feathers on the back. The wings have a large white section that is visible near the rump when the bird is resting, with some loose yellow feathers at the end. Their flight is slow and stately, and the wings look white with a wide chocolate trailing edge. We saw 69 on five days. At Ndutu, we saw some in full breeding plumage in the water in front of a large group of bathing zebras. To observe breathtaking scenes such as this were one of the reasons I wanted to visit Africa.

Grey Crowned Crane - Photo by William Young

Grey Crowned Crane - Photo by William Young Grey Crowned Cranes - Photo by William Young

Grey Crowned Cranes - Photo by William Young Grey Crowned Crane and Plains Zebras - Photo by William Young

Grey Crowned Crane and Plains Zebras - Photo by William Young Grey Crowned Crane and Plains Zebras - Photo by William Young

Grey Crowned Crane and Plains Zebras - Photo by William Young

RailsBlack Crakes were not difficult to see, considering they are rails. We saw them easily at the wetland near our tents at the Momela campsite. They are solid black, with red legs and a yellow-green bill. At Ngorongoro, we saw them walking on the back of bathing Hippopotami, who did not seem to mind being used as stepping stones. Also walking on the Hippopotami was a Common Moorhen. We saw another 20 moorhens at Tarangire. We saw one Purple Swamphen at Lake Manyara, and it looked really big. I had seen this species in Australia. It is purple, with a red bill and red legs.

Black Crake and Three-banded Plover - Photo by William Young

Black Crake and Three-banded Plover - Photo by William Young

BustardsWe saw five species of bustards and had good looks at each. Kori Bustards are the heaviest flying birds in the world. We saw 17 on four of the five days of the trip between the Serengeti and Ngorongoro. They look imperious, because they tend to keep their bill pointing up at about a 30 degree angle while strutting around in the fields. They have a gray neck, black necklace, brown back, and black-and-white patterning on the side of their folded wings. One of the males had his throat poach partially inflated for a sexual display, but he did not seem to be doing much. We saw a female who was being followed by a chick. Another female was sitting on a nest close to the road, and we could see her big yellow eye. The nest was within a circle of rocks that was open at the back to allow the bustard to extend beyond it. I could not tell if there was any nest constructed beneath the large sprawling bird or if the bird and the rocks provided all of the needed protection for the eggs. I found a Kori Bustard feather, and it has beautiful patterning which helps to camouflage the birds. In the Serengeti, we saw a Denham's Bustard, which is only four inches smaller (46 vs. 50 inches) than the huge Kori. It has a dark gray throat, and its neck has rufous which extends to its back. Their wings are much darker than the Kori's, and they have more black-and-white on the folded wing. Bernard had never before seen one.

Kori Bustard - Photo by William Young

Kori Bustard - Photo by William Young Kori Bustard - Photo by William Young

Kori Bustard - Photo by William Young Kori Bustard on Nest - Photo by William Young

Kori Bustard on Nest - Photo by William Young Kori Bustard and Chick - Photo by William Young

Kori Bustard and Chick - Photo by William Young Denham's Bustard - Photo by William Young

Denham's Bustard - Photo by William YoungThe three other bustard species were smaller. We saw nine White-bellied Bustards on three days, with eight in the Serengeti and one near our Naitola campsite. They have a grayish neck and a black-and-white face. We saw one Buff-crested Bustard at Mkomazi, and it had a rounded tan head and a black belly. We saw six Black-bellied Bustards on our final day at Mikumi, and some were very cooperative. One walked across the road near where we had stopped. It had beautifully patterned buff-and-black feathers on its back and wings. Its leg and bill were light colored, and the black on the belly extended up the neck to the chin. The black on the belly was deeply saturated and inky.

White-bellied Bustard - Photo by William Young

White-bellied Bustard - Photo by William Young Black-bellied Bustard - Photo by William Young

Black-bellied Bustard - Photo by William Young

JacanasI saw 20 African Jacanas on five days. They have rufous bodies, white on the chin and throat, and a black eyeline that runs down their neck. They have long legs which stick out behind them when the bird is flying. Sometimes, I could see their long Freddy Kruger toes. Martin saw the much smaller Lesser Jacana, but I did not.

Painted-SnipeThe Greater Painted-Snipe was another species whose beauty surprised me. The two we saw at Dindira Swamp were grayish, with gold on their wings that glistened in the sun. They constantly bob while looking for food. Extending up from the white belly are two white stripes that form a V on their back. They also have a broad white eyeline that runs through their large eyes. The tail is gray, with gold bars.

Greater Painted-Snipe - Photo by William Young

Greater Painted-Snipe - Photo by William Young

Crab PloverWe saw about 50 Crab Plovers on our day in Dar es Salaam. They are large white birds with light colored legs and a thickish black bill. The black eye stands out on the white head. They feed actively, and they look a bit like albino thick-knees. They have some black on the back and wings. They are the only species in their family.

Crab Plover - Photo by William Young

Crab Plover - Photo by William Young

StiltWe saw more than 50 Black-winged Stilts on 8 days. They are the same size and shape as the Black-necked Stilt in North America, but the adults have an all-white head and neck. It was odd sometimes to see them feeding in areas fraught with danger, such as where we were seeing crocodiles and large herds of zebras.

Black-winged Stilt - Photo by William Young

Black-winged Stilt - Photo by William Young

Thick-kneesWe saw thick-knees on only four days. We saw seven Spotted Dikkops in the Serengeti. They have big yellow eyes, yellow legs, and the base of their bill is yellow. The throat is white, but they are entirely spotted on their back. They tend not to move much, which might help with their camouflage. After we saw a couple, we soon realized that more birds were present who were blending in with their background. They behave as if they think they are invisible, and when they lose faith, they scramble away. We saw Water Dikkops on three days. We saw a pair while we were walking near Dindira Swamp. They have a broad gray horizontal bar on their wing, bordered in black. Near where they were, we saw a brown speckled egg that looked as if it had been split open rather than stepped on — the yolk was intact. On our final day at Mikumi, we saw about 30 on the edge of a pond which had Hippopotami in it. One was resting in a position in which I had not before seen. The part of the leg on this bird that is thick is its ankle rather than its knee. Ankles bend backwards, and knees bend forward. I have seen birds bending with their ankle joints pointing backwards, but I had never before seen a bird resting on this joint with its legs pointing forward. It was painful to look at.

Spotted Dikkop - Photo by William Young

Spotted Dikkop - Photo by William Young Water Dikkops - Photo by William Young

Water Dikkops - Photo by William Young Water Dikkop - Photo by William Young

Water Dikkop - Photo by William Young Water Dikkop Egg - Photo by William Young

Water Dikkop Egg - Photo by William Young

Coursers and PratincolesI saw Collared Pratincoles on only three days, but there were between 120 and 200 each time. A lot were at the Hippo Pond at Lake Manyara. They have short legs and long wings, and their flight is tern-like. They are dark, but their rump is whitish. Sometimes when spooked, more than a hundred would swirl around. They sometimes behaved like shorebirds. We saw a lot at the Hippopotamus Pool at Mikumi. In the Serengeti, we saw two Temminck's Coursers. They look delicate and plover-like, with a rufous cap and a black eyeline. We also saw two at Ndutu. We saw 19 Double-banded Coursers, with about 15 around the Naitola campsite. They have a broad black breastband, and above that, a black ring that goes across the breast and all the way around the neck. At Ndutu, we saw one who sat on a pile of dried animal dung. They have black eyes and a black line through the eyes. They are light-colored and blend in with the dried dirt on which they sit and move.

Collared Pratincole - Photo by William Young

Collared Pratincole - Photo by William Young Double-banded Courser - Photo by William Young

Double-banded Courser - Photo by William Young

Plovers and LapwingsPlovers were seen and heard in good numbers on the trip. The count for Crowned Lapwings was 472 on 12 days, but there could have been more. Around our camp at Ndutu, we estimated 420 from March 2 through 4. They have a loud rasping call that reminded me of the related Masked Lapwing in Australia, and we heard it frequently after the sun set when we could not see the birds. They are brown with a white belly and a black-and-white head pattern that makes them appear to wear a white crown. They stand very tall. We saw more than 700 Blacksmith Lapwings, who are a lovely combination of black, white, and gray. At Dindira Swamp, I heard their distinctive tink-tink-tink call that sounds like a lightweight hammer hitting a small anvil. On the section of the trip from the Serengeti to Ngorongoro, we saw 95 Black-winged Lapwings. We had close looks at them at Ngorongoro, and we could see the red eyering, which is diagnostic for separating this species from the similar Senegal Lapwing, whose eyering is yellowish. On our trip to Lake Victoria, we saw eight Long-toed Lapwings, who are lovely. The head and throat are white. They have a bold red eyering and a red bill whose front third is black. The crown, neck, and breast are black, the back is brown, and the belly is white. Their long legs are red, and the bird appears somewhat delicate. In the same general area, we saw three Spur-winged Plovers fly over. Their plumage has a complex black, white, and brown pattern, and they have a black head. At Kilombero, we saw a pair of White-headed Lapwings fly over. They have distinctive black shoulders and black wingtips in flight. In the Serengeti, we saw an African Wattled Lapwing, whose wattles are shorter than those of the Masked Lapwing in Australia. They make the bird look as if it is wearing a fake blond mustache. It is brown, with a streaked cheek and throat.

Blacksmith Lapwing - Photo by William Young

Blacksmith Lapwing - Photo by William Young Black-winged Lapwing - Photo by William Young

Black-winged Lapwing - Photo by William Young Long-toed Lapwing - Photo by William Young

Long-toed Lapwing - Photo by William Young African Wattled Lapwing - Photo by William Young

African Wattled Lapwing - Photo by William YoungThe other plovers we saw were smaller. We saw a Grey Plover in Dar es Salaam, which is the same species as the Black-bellied Plover. We saw a couple of Greater Sand Plovers at Ndutu, who resemble the slightly smaller Lesser Sand Plover. Martin saw a Lesser at the Arusha lakes that I did not. We saw 13 Common Ringed Plovers on three days. We saw them in Dar es Salaam, Ndutu, and near the Momela campsite. They reminded me of Semipalmated Plovers, who are in the same genus. We saw 16 Three-banded Plovers, who are oddly named. They have only two black bands on the breast, separated by a white band. They look distinctive, with a red eyering, gray face, and white crown. We saw them at our Momela campsite, as well as in the Serengeti and at Ndutu.

Three-banded Plover - Photo by William Young

Three-banded Plover - Photo by William Young Little Stint and Common Ringed Plover - Photo by William Young

Little Stint and Common Ringed Plover - Photo by William Young

Sandpipers and AlliesOf the 17 species we saw in this family, we saw more than eight of only four species. I saw an estimated 111 Ruffs. At Ndutu, we saw about 70 relatively close together. They are easy to identify, with their light head and salmon legs. There were another 30 in the lakes around Arusha. We saw 19 Little Stints in five areas, with never more than a half dozen on any given day. They were the smallest shorebird we saw, and they also have a light head. We saw 55 Wood Sandpipers on eight days, with ten each day on the lakes around Arusha and 20 at Dindira Swamp. They look similar to a Solitary Sandpiper and have yellowish legs. The Green Sandpiper was much less common than the Wood. We saw only three on two days. They have darker legs than the Wood and less spotting on the back. They teeter when feeding. The Common Sandpiper lived up to its name and was relatively easy to identify. We saw 21 on seven days. They have a plain brown back and white underparts, with a white slash near the shoulder. They remind me a lot of Spotted Sandpipers without spots (Spotless Sandpipers?) because they constantly bob their tails. I saw one who was standing on a wood railing near the Hippopotamus Pool at Mikumi. Another one in the Serengeti was feeding on the backs of hippos.

Green Sandpiper - Photo by William Young

Green Sandpiper - Photo by William Young Common Sandpiper - Photo by William Young

Common Sandpiper - Photo by William YoungWe saw a lot of the shorebirds on our outing in Dar es Salaam. We saw a couple of Eurasian Curlews, four Whimbrels, a Black-tailed Godwit, two Common Redshanks, a Sanderling, and three Terek's Sandpipers. The Terek's have upcurved bills and walk quickly while crouched, like Groucho Marx. Martin added a Ruddy Turnstone to the list, because he discovered one in a photo he had taken of other shorebirds we were looking at. We saw one Marsh Sandpiper in the Serengeti, who reminded me of a Lesser Yellowlegs. It was feeding in an area where a large number of zebras were bathing. We saw eight Common Greenshanks in two places, and they resembled Greater Yellowlegs. I saw six Curlew Sandpipers on three days, including five in the Arusha lakes. We saw an African Snipe in the wetland area near our tents at Momela, and I could see the snipe stripes. Later in the day, we saw a Common Snipe on the shore of one of the Arusha lakes. The two snipe species look alike, but the Common has more white on its belly.

Ruffs - Photo by William Young

Ruffs - Photo by William Young Eurasian Curlew - Photo by William Young

Eurasian Curlew - Photo by William Young Marsh Sandpiper - Photo by William Young

Marsh Sandpiper - Photo by William Young African Snipe - Photo by William Young

African Snipe - Photo by William Young

Gulls and TernsThe only gulls we saw were four Lesser Black-backed Gulls in Dar es Salaam. The same day, we saw a Caspian Tern and two Saunder's Terns, who look like Least Terns. Martin saw distant Sooty Terns in the same area which I did not see. We saw five Gull-billed Terns there and two when we were at Lake Victoria. On the Lake Victoria boat trip, a Gull-billed Tern appeared to be walking on water. It was standing on a water hyacinth, an introduced species that has caused problems for people who fish the waters. On that same boat trip, we saw an estimated 200 White-winged Terns. Many were not in breeding plumage, and their plumage looked gray rather than white. Some were in breeding plumage, and their body looked blackish. We saw about 20 Whiskered Terns on each of three days — in Dar es Salaam, around Serenity, and at Tarangire. We also saw a few White-winged Terns at Serenity.

SandgrouseSandgrouse look like inflated doves with large eyes and short legs, and they are well camouflaged. We saw a pair of Chestnut-bellied Sandgrouse on the desert road to Ndutu. The male has patterned feathers on his back to blend in with the scenery. The breast is light chestnut, with a thin black vertical line serving as a border on each side. In the same desert, we saw flocks of flying Yellow-throated Sandgrouse and some on the ground. The male is plain, with a tan throat and a black neckband. Some of the brown wing feathers are edged in black, while others are edged in rufous. The female lacks the black neckband, but her feathers have a blizzard of white-and-golden spots. Both sexes have a gray bill and white supercilium. We saw Black-faced Sandgrouse at our Naitola campsite. They have the busiest looking plumage of the three sandgrouse, with a black face, a black-edged white border to the breast, both a black and a white supercilium, and what look like broken concentric circles on the wings. The bill is reddish, and they have bare yellow skin around the eyes.

Chestnut-bellied Sandgrouse - Photo by William Young

Chestnut-bellied Sandgrouse - Photo by William Young Yellow-throated Sandgrouse - Photo by William Young

Yellow-throated Sandgrouse - Photo by William Young Black-faced Sandgrouse - Photo by William Young

Black-faced Sandgrouse - Photo by William Young