- About

- Library

-

Essays

Eric Dinerstein William C. Young

- Plants

- Birds

FIELD NOTES FOR ANTARCTICA, SOUTH GEORGIA, THE FALKLAND ISLANDS, AND USHUAIA AND BUENOS AIRES, ARGENTINA

January 6 to 27, 2016

William Young

INTRODUCTION

ITINERARY

BIRD FAMILIES

BIRD FAMILIES SEEN ONLY IN BUENOS AIRES

MAMMALS

OTHER FLORA AND FAUNA

GENERAL COMMENTS

SIGHTINGS LIST - ANTARCTICA-SOUTH GEORGIA-FALKLANDS-USHUAIA

BIRD SIGHTING LIST - BUENOS AIRES

INTRODUCTION

In late 2014, I heard about a 2016 trip to Antarctica, South Georgia, and the Falklands being run by Victor Emanuel Nature Tours (VENT). The leader would be Michael O'Brien, who is the son of my first cousin Barbara. I go to the O'Brien's each year for Christmas brunch, and I spoke with Michael and his father Paul about the possibility of going. Michael's brother John, who lives in Houston, also thought of going. I had to make the decision by early April, and I put down a deposit. Paul did also, and we planned to room together. Later, John decided to go, so the trip would involve four members of our family.

Michael, John, and Paul are all extraordinarily skilled birders. Michael is a tour leader for VENT, and the VENT contingent of about 10 people would be on the boat the Sea Adventurer with about a hundred other passengers. The trip was run by the tour company Zegrahm. The name comes from the letters of the names of the founders, one of whom was Peter Harrison, the author of the pioneering bird reference book Seabirds. The company has been in business since 1990. I found out during the trip that Peter Harrison is revising his Seabirds guide, in part because of the substantial number of taxonomic changes to seabird species since the original guide was published in 1983.

At Christmas brunch in 2015, I talked with Paul and Michael about our trip, which would start in less than two weeks. John was not at the brunch, but he would join Paul and me in Buenos Aires where we would be spending a couple of days before flying south to Ushuaia on the southern tip of South America. Michael would not be on the Buenos Aires trip and was flying directly to Ushuaia.

On January 5, I left home in Arlington, Virginia, and flew to Atlanta, where I met up with Paul, who had flown there from Baltimore. We took an overnight flight to Buenos Aires. A lot of other people on our flight were heading to Antarctica. We were met at the Buenos Aires airport by Hernan Gõni from VENT, who would be one of our guides in Buenos Aires. The other guide was Emiliano Garcia Loyola, and both were very knowledgeable birders and naturalists (and nice people). Hernan took us to the Hotel Lafayette in downtown Buenos Aires. After we got settled and had lunch, we got into a bus and went to the Reserva Costnera Sur (South Beach Reserve) from 2 to 7 p.m. The South Beach Reserve was 2.5 miles from our hotel and remarkably birdy. We probably walked less than a half a mile, because we were constantly stopping to look at birds. This public park had a lot of joggers and people with baby carriages. The following day, we drove 45 minutes to the Otamendi Nature Reserve where we stayed from 7:45 a.m. to 5 p.m., with a stop in the middle to drive to a facility where we had lunch. Otamendi has dusty dirt roads, which was unpleasant when cars drove by and stirred up the dust. It has a combination of forests and wetlands, and as on the previous day, we saw an excellent array of species.

The temperatures in Buenos Aires were in the mid-80s, which must have been unusually hot, because a lot of news programs had stories about what people were doing to cope with the heat. The morning of the 8th was cooler and drizzly as we boarded a bus to go to the airport to catch our flight to Ushuaia. We arrived in Ushuaia in the early afternoon and were met with sunny weather that was intensely windy. We got on another bus and drove the short distance from the airport through town to Arakur Resort, which was on a hill that overlooked Ushuaia. The backdrop with the mountains and glaciers was beautiful. We met up with Michael, had a late lunch, and then took the bus to town for a quick walk. We did not have much time, because we needed to be back for a welcoming reception and dinner sponsored by Zegrahm. We spent about an hour walking along the water before heading back.

The following day, we took a bus to Tierra del Fuego National Park. While there, I went to a small post office where I bought some bird stamps for my collection. We were running late on our trip to Tierra del Fuego, because we were told we needed to be back at the ship by 4 p.m. in order to take off on our expedition at 6 p.m. The park was about 45 minutes from the ship, and we were still there at 4. It turned out that there was no need to rush, because the winds were blowing at 60 knots, with gusts above 80. We could not leave the port, both for fear of what could happen to the ship, but more for what could happen to the port facilities if the ship were being blown around. We were not on one of the large cruise ships that could hold more than 600 passengers. Our ship held about 110, and it also had 75-80 staff on board. We ended up being anchored in the port for an unscheduled 27 additional hours, during which time we went for a walk in the wind in Ushuaia, going in a big loop around the water. To use the words of the captain, we finally "escaped" the harbor at 9 p.m.

The next day featured a spectacular array of seabirds, with thousands of albatrosses and shearwaters. There were also a lot of prions, petrels, storm-petrels, and other species. Before the trip, I bought a guide to Antarctic wildlife that talks about typical trips from Ushuaia to Antarctica. The book divides the trip into three sections. The water immediately south of Ushuaia is called the Beagle Channel, named after Darwin's ship. The channel stretches for about 150 miles. South of that is the Drake Passage, which runs all the way to the South Shetland Islands of Antarctica. We did not take this route on the way down. Instead we veered northeast and headed toward the Falkland Islands, which are about 420 miles away. Because of the delay in leaving port and the strong headwinds we encountered, we were behind schedule. We also were slowed because one of the motors on the ship had developed problems a few weeks before our expedition and was running at only about 90 percent of capacity. Had we tried to go fast to make up time, we would have run the risk of blowing that engine entirely. So we ended up making only one zodiac landing in the Falklands on Saunders Island. Zodiacs are large rubber rafts with an outboard motor. Each one can accommodate about eight to ten people, plus the driver who stands in the back. In calm water, they are capable of speeds of up to 20 knots. (One knot = 1.15 mph.) We could not go nearly that fast in the zodiac around the Falklands, where the water was choppy. It was not uncommon for the zodiac to bounce and send a wall of water on some or all of its passengers. The wind at Saunders Island was fierce, and while we were on the beach, we got sandblasted. The wind was not as intense when we got off the beach and hiked up a grassy hill.

From the 13th through the 15th, we travelled southeast from the Falklands to South Georgia Island, a distance of close to 1,000 miles. In the early evening of the 15th, we reached Shag Rocks, which are six small islands 150 miles west of the main island of South Georgia. True to their name, they were covered with thousands of South Georgia Shags. We also started to see our first icebergs, including one really large one that was right behind Shag Rocks. At this point, I began to feel as if I were in the Antarctic region.

On the 16th, we made our first landings on South Georgia. In the morning, our ship passed both Bird Island and Willis Islands, which have many glaciers. In the late afternoon, we went to Salisbury Plain, which is an extraordinary wildlife area. It has hundreds of thousands of King Penguins and enormous numbers of Antarctic Fur Seals. The weather was overcast with snow flurries. Michael brought the VENT group up a treacherous grassy hill to a lookout over a lake. Paul fell on the way up, so I decided I did not want to go and instead stayed on level ground with the penguins. We returned to the ship, and after dinner, we got back into the zodiacs and went to Prion Island. The weather was still overcast with light snow. We ascended a long boardwalk to visit an area where Wandering Albatrosses and other seabirds nest.

The next day was sunny, and we went by zodiac to Grytviken. A lot of the places have Norwegian names because of the prominence of Norwegians in whaling during the early 20th century. Grytviken has a small number of buildings, including a museum, a church, and a post office. It also has a small graveyard that contains the grave of the explorer Ernest Shackleton as well as the ashes of his comrade Frank Wild. I went to the post office and bought more than $50 worth of cards and bird stamps. I was there before other people from our group came, so I was able to spend 20 minutes alone with the man in the post office to see everything he had for sale.

Grytviken - Photo by William Young

Grytviken - Photo by William Young Grytviken - Photo by William Young

Grytviken - Photo by William YoungAfter lunch, the ship went to a small settlement called Stromness where people could hike a mile to a waterfall. Upon reaching the waterfall, people could either return to the zodiac or continue along a much longer route that is the same one Shackleton took when he was on South Georgia. I decided to forego both the waterfall and the Shackleton hike, and instead, stay on the boat and try to absorb the incredible scenery. This also gave me a chance to recharge my batteries a bit before the following day when we would be visiting a King Penguin colony. Once the waterfall people returned, the ship repositioned itself a few miles away to pick up the people who were doing the long hike. Apparently, these hikers arrived at their destination about an hour ahead of schedule, and the ship had not yet arrived. Before it did, some of the hikers wondered whether they might have a Shackleton experience that was much more realistic than they anticipated.

Stromness - Photo by William Young

Stromness - Photo by William YoungThe 18th was a magical day. We started by taking a zodiac to Saint Andrews Bay, which has 400,000 to 500,000 King Penguins. There is all sorts of other wildlife there, and when you add in the mountains and glaciers in the background, it is one of the most extraordinary wildlife experiences I have ever had. In the afternoon, we made our final landing in South Georgia at Gold Harbour, which has King Penguins, Elephant Seals, and lots of other wildlife on the beach.

From the 19th to the 21st, we travelled through the Scotia Sea from South Georgia to the Antarctic Peninsula, a journey of about 375 miles. In the open ocean far from land, the number of seabirds diminished. On the evening of the 21st, we approached Elephant Island, which is about 150 miles north of the Antarctic Peninsula. The geologist on board said that one does not have to be on the peninsula to be in Antarctica — Japan is not on the Asian mainland, but people in Japan are considered to be in Asia. We were near a place called Point Wild, where a bust of a Chilean military figure has been erected. It looks very out of place. Michael and Paul decided they did not want to take a zodiac ride to get closer to Point Wild, but John and I went. Because it was getting dark, I decided that there was no point in bringing my camera. John brought his, but because the seas were so rough, we got splashed with a lot of salt water. Some water got onto his camera and fried the motor. Fortunately, he was able to borrow another camera body for the remainder of the trip from Michael. My glasses got covered with salt water, and the light was too dim to see much. I had to crouch in the zodiac which was bouncing in the rough seas, and the zodiac driver did not maneuver the craft around so that everyone on both sides could see Point Wild. When in the zodiacs, we were, as always, wearing waterproof trousers, boots, and coats, but that did not make getting soaked any more pleasant.

On the 22nd, we finally walked on Antarctica. That evening, we landed at Brown Bluff. I have friends in Maryland who had given me a small plastic penguin as a bon voyage gift. I brought it with me to Brown Bluff, placed it on a rock, and took some photos of it with Adelies in the background. This was our first colony of Adelie Penguins. We were lucky the following day, because the weather was sunny, and the water was dead calm for one of the few times on the expedition. We started by going to Paulet Island, which is within a few miles of the Antarctic Peninsula. It has a large Adelie Penguin colony as well as many other nesting seabirds. This was by far my favorite destination in Antarctica. That afternoon, we took advantage of the calm waters to take a zodiac ride around the Weddell Sea, where we saw whales, seals, and other wildlife at close range.

Penguin Toy in Antarctica - Photo by William Young

Penguin Toy in Antarctica - Photo by William Young Paulet Island - Photo by William Young

Paulet Island - Photo by William YoungThe calm seas did not last. The next day, the people on the ship were supposed to be split into two groups, with one group going to Hardy Cove and the other going to Fort Point. Both of these destinations are in the South Shetland Islands. I wanted to go to Fort Point to see the Chinstrap Penguin colony, but I was assigned to the group scheduled to go to Hardy Cove. Zodiacs were supposed to shuttle people between the two locations so that everyone could see both. I was on the first zodiac that landed at Hardy. The seas were rough, and I did not want to stay there. When the second zodiac arrived, I got on and went to Fort Point. The seas soon became so rough that all further zodiac trips between the islands were cancelled. John was in the second zodiac, so he never got to Fort Point. The water had become choppy, and it was the choppiest next to our ship where we needed to get off. Our zodiac driver was knocked down as she reached for the dock to secure us. This was our final zodiac ride of the expedition, and I was not sorry that we would not have any more.

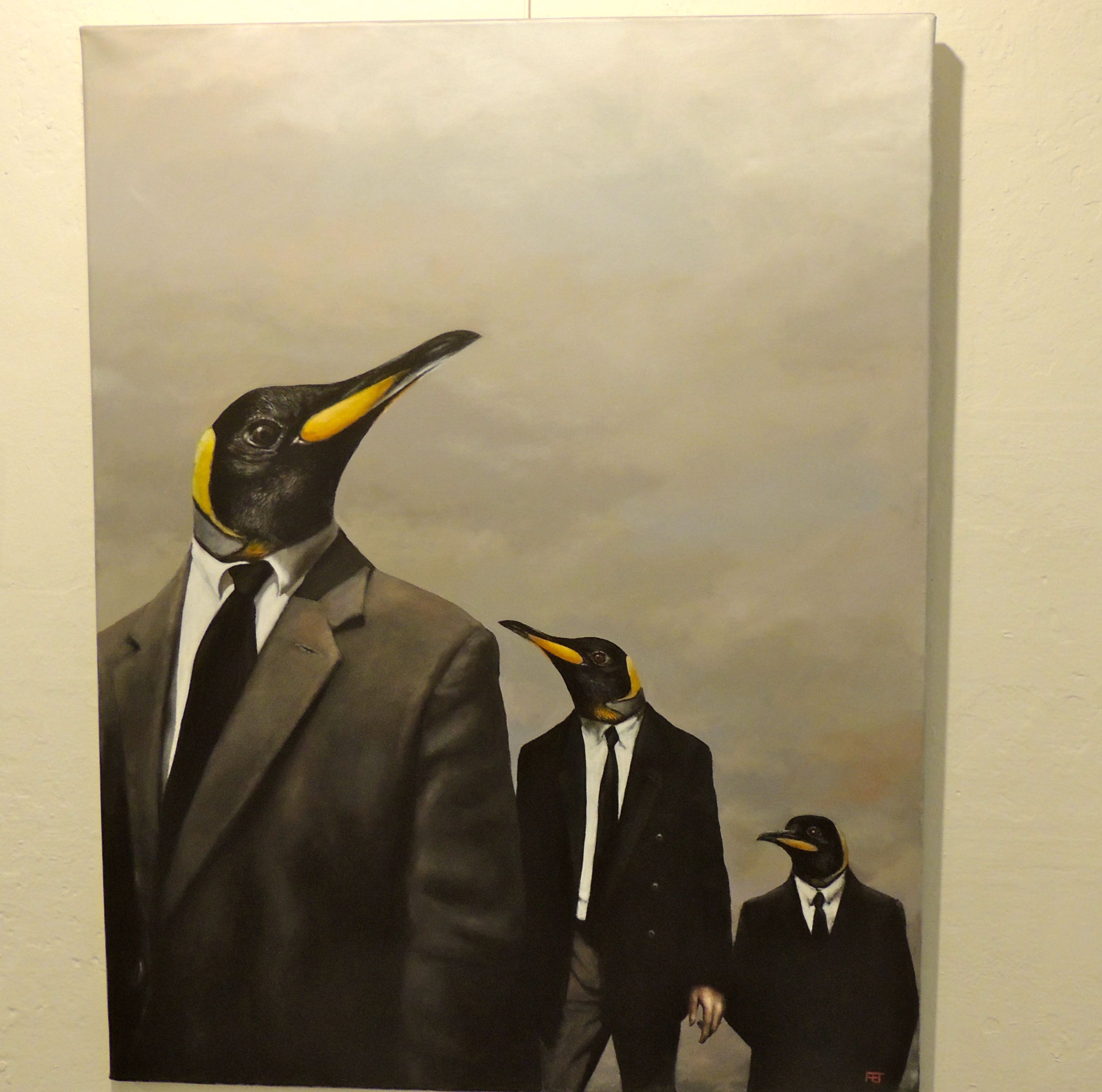

We spent the remainder of the expedition heading back to Ushuaia. As we got through the Drake Passage and into the Beagle Channel, the water became calmer. Our final evening at sea was clear and pleasant. We could see Tierra del Fuego to our right and the mountains of Chile to our left. We arrived at the dock just before midnight on the evening of the 26th. My flight back to Buenos Aires was at 1:45 the next day. The people on the ship were given the option of going to a museum or hiking up a glacier. Because I had already packed my hiking boots and did not feel like being tired and sweaty before my long trip home, I decided to spend the final morning at the museum and walking around Ushuaia. The museum was in an old prison, and a lot of the artwork was displayed in tiny rooms that used to be the cells. Much of it had a penguin theme, ando I took a lot of photos. One can imagine how awful it must have been to be incarcerated in these tiny (8' x 8') cells 100 years ago with no heating in the winter. We then walked around the city for awhile, and I picked up a little metal charm with an albatross on it that was being given away by a local jewelry store. We then got in the bus and went to the airport.

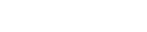

Ushuaia - Photo by William Young

Ushuaia - Photo by William Young Ushuaia - Photo by William Young

Ushuaia - Photo by William Young Ushuaia - Photo by William Young

Ushuaia - Photo by William Young Prison Museum - Photo by William Young

Prison Museum - Photo by William Young Penguin Art - Photo by William Young

Penguin Art - Photo by William Young Penguin Art - Photo by William Young

Penguin Art - Photo by William Young Penguin Art - Photo by William Young

Penguin Art - Photo by William Young Penguin Art - Photo by William Young

Penguin Art - Photo by William Young Penguin Clothes - Photo by William Young

Penguin Clothes - Photo by William YoungAfter we arrived at Buenos Aires, we had a bit of a layover, so Michael, Paul, and I had dinner in what might have been the only decent restaurant in the airport. John was taking a direct flight back to Houston, so he had to go to a different terminal. I walked the entire length of the terminal from where we were leaving, and there were far more places that offered high quality drinks than high quality food. On the plane back to Atlanta, the woman who was sitting next to me at the beginning of the flight talked to a flight attendant and managed to get her seat changed to one in the front so that she could be with her husband. I was then able to stretch out on her seat and mine, and I managed to sleep a bit before returning to the US. In Atlanta, I said good-bye to Michael and Paul, and we all headed our separate ways. I got back to Washington at about 9:15 a.m. and was home by 10.

ITINERARY

Jan 6 Reserva Costnera Sur (South Beach Reserve)

Jan 7 Otamendi Nature Reserve

Jan 8 Flew to Ushuaia, Ushuaia Harbor

Jan 9 Arakur Resort Trails, Tierra del Fuego National Park

Jan 10 Ushuaia Harbor Loop, Beagle Channel

Jan 11 Travel from Ushuaia to Falklands

Jan 12 Pelagic Birding on West Side of Falklands, North Side of Saunders Island

Jan 13-14 Travel toward South Georgia

Jan 15 Travel toward South Georgia, Passed Shag Rocks

Jan 16 Travel toward South Georgia, Bay of Isles, Salisbury Plain, Prion Island

Jan 17 Hercules Bay, Grytviken, Stromness

Jan 18 Saint Andrews Bay, Gold Harbour

Jan 19-20 Travel through Scotia Sea

Jan 21 Travel through Scotia Sea to Elephant Island, Point Wild

Jan 22 Travel through Drake Passage to Antarctic Sound, Brown Bluff

Jan 23 Paulet Island, Weddell Sea

Jan 24 South Shetland Islands, Half Moon Island, Fort Point, Hardy Cove

Jan 25 Travel through Drake Passage

Jan 26 Travel through Drake Passage, Beagle Channel

Jan 27 Ushuaia, Buenos Aires Airport

BIRD FAMILIES

WaterfowlWe saw very few ducks, geese, and swans after we left Argentina. At the South Beach Reserve in Buenos Aires, we saw two Coscoroba Swans swimming close to the shore. They have a shorter neck than most swans and a reddish-pink bill. They look gooselike. We also saw a pair swimming with three cygnets. At Tierra del Fuego, a pair of Black-necked Swans came relatively close to the shore. They look like a cross between a Mute Swan and a Black Swan, with the long curved black neck and a white body. From a distance, the bill looks red, but the red part is a bulb over the bill.

Coscoroba Swans - Photo by William Young

Coscoroba Swans - Photo by William Young Black-necked Swans - Photo by William Young

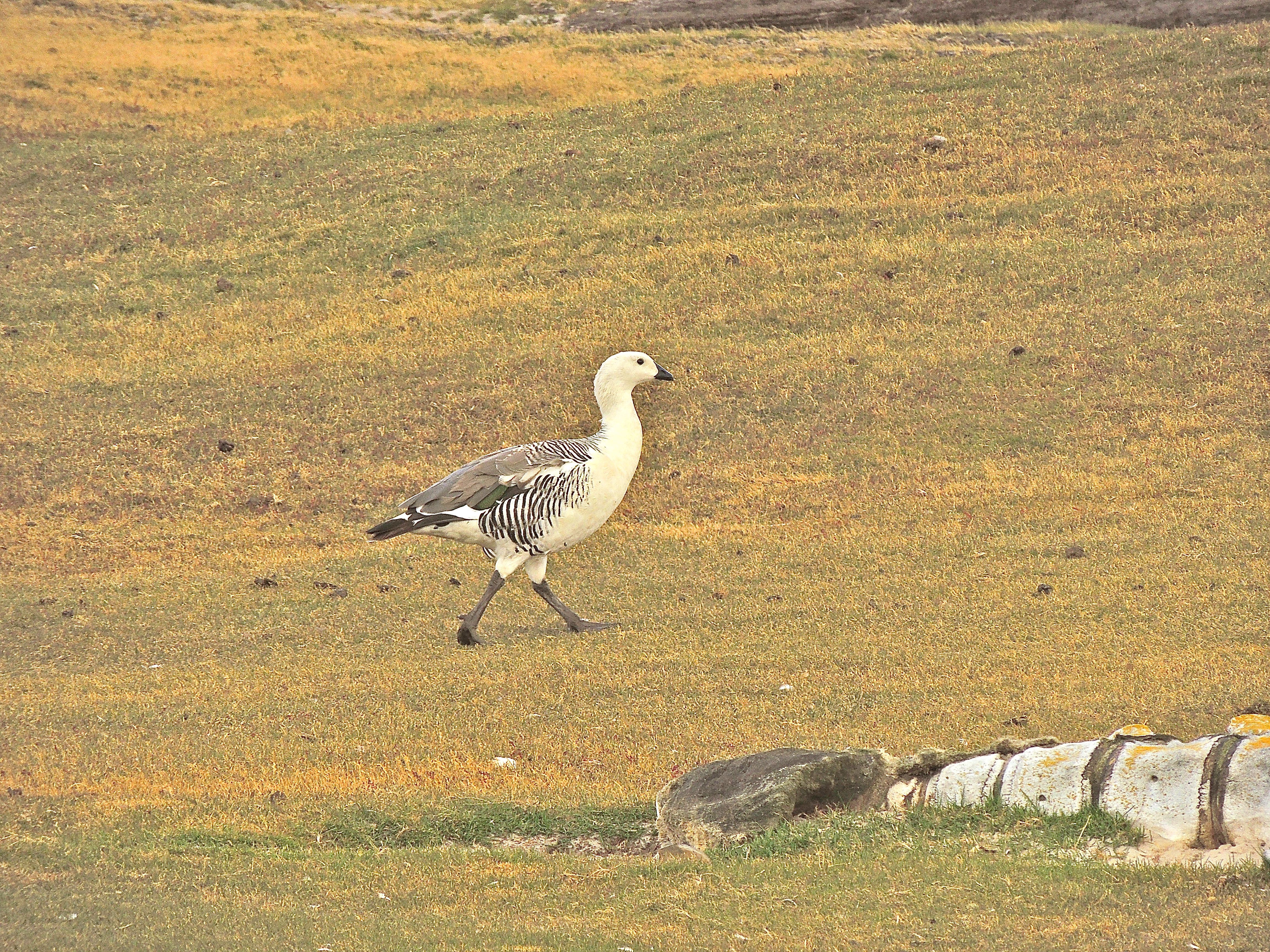

Black-necked Swans - Photo by William YoungSome of the Argentine geese are very pretty. A pair of Kelp Geese was near the shore in Ushuaia. The male is snow white, with black eyes, a black bill, and bright yellow feet which I could see as he stood on rocks covered with vegetation. The female has dark chocolate upperparts and black underparts with white barring. She has both a white wing patch and a dark green speculum. Her tail is white, and her bill is pink. She also has a whitish eyering. Her feet are bright yellow, and I could see her black nails. The pair looked chunky and was eating vegetation on and near the rocks. At Tierra del Fuego, I saw a beautiful family of Ashy-headed Geese. The male and female look alike. They are grayish down to the breast, with the forehead lighter than the neck — the head appears to be illuminated. The breast is rufous with faint barring. The belly and flanks are white, but a broad area on the flanks has black barring. They were accompanied by two goslings who had brownish backs and appeared to have a brown Mohawk. At one point, the entire family walked onto the shore. The adults have orange feet, while the feet of the young are black. There is a post office near where the geese came onto the shore, and I bought an Ashy-headed Goose bookmark — apparently, these geese are a popular species in the park. We also saw Upland Geese in the park, but we subsequently had better looks at them on Saunders Island. I saw a male who had an all white head and breast like the male Kelp Goose. The back and flanks had black barring, the wings looked grayish brown, and the tail was white with a black tip. The bill, eyes, and feet were black. The bills on all of these goose species looked relatively small and delicate.

Female Kelp Goose - Photo by William Young

Female Kelp Goose - Photo by William Young Male Kelp Goose - Photo by William Young

Male Kelp Goose - Photo by William Young Female and Male Kelp Geese - Photo by William Young

Female and Male Kelp Geese - Photo by William Young Ashy-headed Geese - Photo by William Young

Ashy-headed Geese - Photo by William Young Ashy-headed Geese - Photo by William Young

Ashy-headed Geese - Photo by William Young Male and Female Upland Geese - Photo by William Young

Male and Female Upland Geese - Photo by William Young Male Upland Goose - Photo by William Young

Male Upland Goose - Photo by William YoungSteamer-ducks are difficult to identify to species. There are flightless ones and flying ones, and the differences are subtle. In addition, Jim Wilson said that some flightless ones can fly, which suggests interbreeding. I never saw any of them steaming through the water, which is the basis for their name. At Tierra del Fuego, we saw seven distant steamer-ducks on the water who were identified as Flying. We later saw a much closer group who were Flightless. Both species are large and round, with gray plumage. The female of the Flying has a yellow bill which contrasts with the bright orange bill of the male, while the bills of both the male and female Flightless are bright orange. The wings on the Flightless are shorter and stubbier, but that can be difficult to see in the field. The Flying is the only one found in freshwater. When we arrived at Saunders Island, I saw a pair of the endemic Falkland Streamer-Ducks, who are flightless. Our zodiac driver Nate took us into a cove near where we had disembarked, and a pair was swimming near the shore. A couple of other people who did not come up to see the Black-browed Albatross colony saw Falkland Steamer-Ducks on another part of Saunders Island, but the birders who were in other zodiacs did not see them.

Flying Steamer-Ducks - Photo by William Young

Flying Steamer-Ducks - Photo by William Young Flightless Steamer-Ducks - Photo by William Young

Flightless Steamer-Ducks - Photo by William YoungOn the windy day that kept us stuck in Ushuaia, we walked around the waterfront and saw other species of ducks. Crested Ducks were fairly common. They are grayish brown with a red eye. One can see a crest that hangs on the back of the head. In flight, they show white in their wings. We saw Red Shovelers, who have a gray head, light eyes, and brown sides with black speckling. They show a lot of green in the speculum, and they have a large black shoveler bill. The Yellow-billed (or Speckled) Teal is noticeably smaller than the previous two species. They are all brown with a bright yellow bill. We saw three species of teals in Buenos Aires. Some Silver Teals were swimming close to the shore in water with thick vegetation. They are brownish with a black cap on a white head and neck. A pair of Ringed Teals was sitting on a tree branch that had fallen into the water. The male has a blue bill and a broad cinnamon stripe above his gray flank. The female is much plainer, being brown with a broad white eyestripe. At Otamendi, we saw two flying Brazilian Teals, whose large blue-green speculums glistened in the sun. The only waterfowl I saw after the Falklands were the endemic South Georgia Pintails, who are brown ducks with a bright yellow bill. The head looks delicate. I saw some near the shore at Grytviken and managed to take a photo that came out to be much more dramatic than it appeared when I shot it. A pintail was standing on some rocks, and the angle of the photo makes the duck stand out as if on a wild rocky shore instead of being in a little protected cove.

Crested Duck - Photo by William Young

Crested Duck - Photo by William Young Red Shovelers - Photo by William Young

Red Shovelers - Photo by William Young Red Shoveler - Photo by William Young

Red Shoveler - Photo by William Young Yellow-billed Teal - Photo by William Young

Yellow-billed Teal - Photo by William Young Silver Teals - Photo by William Young

Silver Teals - Photo by William Young Ringed Teals - Photo by William Young

Ringed Teals - Photo by William Young South Georgia Pintail - Photo by William Young

South Georgia Pintail - Photo by William Young South Georgia Pintail - Photo by William Young

South Georgia Pintail - Photo by William Young South Georgia Pintail - Photo by William Young

South Georgia Pintail - Photo by William Young

GrebesIn Buenos Aires, we saw a group of White-tufted Grebes. We were looking into the sun, but even in the glare, I could see they have brownish flanks and a large white ear patch. At the park in Tierra del Fuego, we saw Great Grebes. They are quite large with a long slender neck. A pair was courting, and one appeared to be passing a small fish to the other. They have a black body, a black head, and a rufous neck. The bill is long and pointed.

White-tufted Grebe - Photo by William Young

White-tufted Grebe - Photo by William Young Great Grebes - Photo by William Young

Great Grebes - Photo by William Young

PenguinsI might have seen literally a million penguins on this trip. The numbers were so large and spread out that providing an exact count is impossible. Seeing penguins at sea can be difficult and tends not to be satsfying. They often are porpoising, which does not allow good views. Their dark backs blend in with the dark surface of the sea. They are more likely to be diving than sitting on the surface. To see penguins well, one must go to the colonies where they breed or congregate. We did not see any Emperor Penguins on the trip. They are found farther inland in Antarctica, and the only ones we had a chance to see were young birds who dispersed from their breeding area.

By far, we saw more King Penguins than any other bird species. They are the second largest penguin species in the world, behind the Emperor. They were on the Falklands and South Georgia, but not on the Antarctic Peninsula. Jim estimated that there were about 80,000 breeding pairs on Salisbury Plain in South Georgia and about a quarter of a million birds altogether. There were only 318 left at Salisbury early in the 20th century after the carnage committed by the whalers and others, but the numbers recovered. Saint Andrews Bay in South Georgia had an estimated 400,000 to 500,000 King Penguins. An adult King Penguin stands almost three feet tall and can weigh more than 30 pounds. The adult birds have a yellow-orange band that goes from the chin to the breast and a teardrop shaped yellow-orange mark around their ear. They also have a yellow stripe on their black bill. The males and females have similar plumage, but the males are larger. The young birds look like Sasquatch, being covered with what looks like brown hair. Some are fatter than the adults. The birds take two or three years to pass into full adult plumage, and the second year birds look like adults, but have lemon yellow areas instead of yellow-orange areas.

King Penguins - Photo by William Young

King Penguins - Photo by William Young King Penguins - Photo by William Young

King Penguins - Photo by William Young King Penguin - Photo by William Young

King Penguin - Photo by William Young King Penguin - Photo by William Young

King Penguin - Photo by William Young Male (left) and Female (right) King Penguins - Photo by William Young

Male (left) and Female (right) King Penguins - Photo by William Young Second-year King Penguin Sleeping - Photo by William Young

Second-year King Penguin Sleeping - Photo by William YoungI saw King Penguins in countless plumages. Penguins engage in catastrophic molts, which means they grow all of their feathers at once. During this time, they cannot go into the water. Often the old feathers do not fall out until the new ones have grown in, which results in strange and hilarious looking intermediate molt patterns. Some King Penguins looked as if they were wearing a fur stole around their shoulders. One had a mane like a male lion. Some appeared to have long hair on their bellies. One had all brown fur-like feathers with a white throat that looked like a dickey. One appeared to be wearing white underpants. Some had fur-like feathers only on their head. Some appeared to be wearing yellow earmuffs. We saw a small group on Saunders Island who were mostly birds two years or older. One chick still had its brown plumage and was insistently begging for food. One adult was all alone, walking up a hill. During the trip, we tended to see large groups of penguins together, so seeing one walking up a hill by itself looked odd.

King Penguin Juvenile - Photo by William Young

King Penguin Juvenile - Photo by William Young King Penguin Juvenile - Photo by William Young

King Penguin Juvenile - Photo by William Young King Penguin Molting - Photo by William Young

King Penguin Molting - Photo by William Young King Penguin Molting - Photo by William Young

King Penguin Molting - Photo by William Young King Penguin Molting - Photo by William Young

King Penguin Molting - Photo by William Young King Penguin Molting - Photo by William Young

King Penguin Molting - Photo by William Young King Penguin Molting - Photo by William Young

King Penguin Molting - Photo by William Young King Penguins Molting - Photo by William Young

King Penguins Molting - Photo by William Young King Penguins - Photo by William Young

King Penguins - Photo by William Young King Penguins - Photo by William Young

King Penguins - Photo by William YoungAt Saint Andrews, we walked through an area littered with white King Penguin feathers. The feathers were very small and looked matted. They did not look like feathers of the birds of North America. A King Penguin's back looks like a computer circuit board, with a lot of very small knobs packed tightly together. A penguin's plumage is the densest of any bird family. They have feathers all over their body, except their bill and feet. The silky outer surface helps to reduce friction. The outer feathers overlap tightly like fish scales, protecting a layer in which air is trapped for insulation. The insulation has evolved to keep penguins warm in both air and water. King Penguins and other penguin species are under serious threat because of climate change. In warm weather, they can easily overheat. Some penguins suffering from heat stress will eat snow to cool down, if available. Also, their ability to effectively forage for food can be affected by changes in ocean temperature of as little as several tenths of a degree Celsius, and the oceans are expected to warm by more than that.

King Penguin Feathers - Photo by William Young

King Penguin Feathers - Photo by William Young King Penguin's Back Feathers - Photo by William Young

King Penguin's Back Feathers - Photo by William Young

As with all other penguins, the King Penguin has a stiff tail. The tail contains a fusion of bones that taper to a point. Penguin tails help them to balance when standing upright. The stiff tail also helps them to steer when swimming. One of the penguins had a bloody breast, possibly from a scrape on a rock, a bite from a seal or other creature, or a fight with another penguin. The colonies typically had skuas, giant petrels, and sheathbills prowling around, hoping for a penguin meal. These species build their nests within the penguin colony, which saves them commuting time. We saw skuas eating dead penguins, and we saw the remains of penguins who had already been eaten. I saw the bottom of the feet of dead King Penguins. They are black and have a lot of little nipples close together for traction. King Penguin Tail - Photo by William Young

King Penguin Tail - Photo by William Young Bloodied King Penguin - Photo by William Young

Bloodied King Penguin - Photo by William Young King Penguin Wound - Photo by William Young

King Penguin Wound - Photo by William Young King Penguin with Stained Breast - Photo by William Young

King Penguin with Stained Breast - Photo by William Young King Penguin Foot - Photo by William Young

King Penguin Foot - Photo by William Young King Penguin Footprints - Photo by William Young

King Penguin Footprints - Photo by William Young King Penguin and Southern Elephant Seals - Photo by William Young

King Penguin and Southern Elephant Seals - Photo by William YoungSome of the behavior of the King Penguins was amusing. There was a fast running stream at Saint Andrews, and I saw a King Penguin swimming down as if it were white water rafting, having to maneuver around rocks. A giant petrel also did this. Some of the King Penguins were at the beach and swam out a short distance before appearing to body surf in with the tide. As the water receded, they stood up and walked toward the sand, only to return to the water to try again. They did not appear to be looking for food when they did this, and I wondered if they were doing it to keep cool, to bathe their feathers, or simply because it was fun. One King Penguin was standing on a small mound and looked around from the slightly superior perch. The penguins sometimes lifted their heads and vocalized, and with some, I could see their breath condensing as they did this. Many of the penguins were lying on their stomach, possibly because of heat stress. They can stay cooler by exposing the bottom of their feet to the air. Some of the young ones were doing this, and even though they were probably only sleeping, they looked as if they could not get up. A lot of the young birds waved their flippers about as if trying to fly. They probably did this to strengthen the muscles they would need for swimming. Some people on our trip had cameras with tripods, and the penguins sometimes came close to examine them. The female King Penguins have a large flap of skin on their belly which can be used to cover an egg resting on their feet. I saw quite a few distended belly flaps. Some of the birds had eggs, and others had newborn chicks. Because the reproductive cycle of these penguins can last more than a year, one can see most phases of it when visiting a colony. I also saw a pair engaged in courtship, which involves the male and female getting close together and doing what looked like a slow contact improvisation dance, snaking their heads and bodies around one another. Seeing all of these King Penguins and their behaviors at Saint Andrews with mountains and glaciers in the background was one of the highlights of my trip.

King Penguin Standing on Mound - Photo by William Young

King Penguin Standing on Mound - Photo by William Young King Penguin - Photo by William Young

King Penguin - Photo by William Young King Penguin - Photo by William Young

King Penguin - Photo by William Young King Penguin - Photo by William Young

King Penguin - Photo by William Young King Penguins - Photo by William Young

King Penguins - Photo by William YoungOn the beach at Saint Andrews, I photographed a King Penguin with the third and fourth largest penguin species in the world — the Gentoo and the Chinstrap. The Gentoos are the larger of the two. They have a white patch above each eye. The bill is red, and their feet are orange with black toenails. Unlike the King and the Adelie whose young look as if they have brown fur, the young Gentoos look like miniature gray versions of the adults. We saw a colony of probably a couple thousand on Saunders Island — the first large penguin colony of the trip. We also saw them in South Georgia and on the Antarctic Peninsula. The adults sometimes point their bills skyward and vocalize. Some had red marks on their underside that looked like blood. They sometimes get these marks when sliding on their bellies. At Brown Bluff, I saw a small Gentoo Penguin being nipped at and chased by an adult. It was scrawny and may have been looking for its mother, and it probably was not going to survive. One Gentoo chick was resting at an adult's feet, wrapped around an egg. One of the naturalists said that the second egg probably would not hatch. The eggs are laid and hatch at different intervals, so there still was hope. Gentoos make their nest out of pebbles, and we saw some doing nest maintenance by picking up small stones and repositioning them. Also at Brown Bluff, I saw an adult sleeping next to a rock with three young penguins sleeping with their heads resting on the rock. Gentoos are the fastest swimming birds in the world, with some reaching speeds of more than 20 miles per hour. Michael and I observed some swimming underwater at Fort Point, and they moved around like little torpedoes. When we were at sea, we sometimes would encounter them porpoising.

Gentoo, Chinstrap, and King Penguins - Photo by William Young

Gentoo, Chinstrap, and King Penguins - Photo by William Young Gentoo Penguin - Photo by William Young

Gentoo Penguin - Photo by William Young Gentoo Penguin - Photo by William Young

Gentoo Penguin - Photo by William Young Gentoo Penguins - Photo by William Young

Gentoo Penguins - Photo by William Young Gentoo Penguins - Photo by William Young

Gentoo Penguins - Photo by William Young Gentoo Penguins - Photo by William Young

Gentoo Penguins - Photo by William Young Gentoo Penguins Swimming - Photo by William Young

Gentoo Penguins Swimming - Photo by William Young Gentoo Penguin on Nest - Photo by William Young

Gentoo Penguin on Nest - Photo by William Young Gentoo Penguin Feeding Chick - Photo by William Young

Gentoo Penguin Feeding Chick - Photo by William Young Gentoo Penguin with Chick and Egg - Photo by William Young

Gentoo Penguin with Chick and Egg - Photo by William Young Gentoo Penguin with Chick and Egg - Photo by William Young

Gentoo Penguin with Chick and Egg - Photo by William Young Gentoo Penguin with Three Sleeping Chicks - Photo by William Young

Gentoo Penguin with Three Sleeping Chicks - Photo by William YoungFort Point in the South Shetland Islands featured the funniest thing I saw during the trip. We saw only a few Chinstrap Penguins in South Georgia — mostly singles at a variety of areas. They are comical looking, resembling porky German soldiers during World War One wearing a helmet with a chinstrap. One on the beach at Saint Andrews was lying around and later got into a conflict with a King Penguin. We did not see any numbers of them until we arrived at the Antarctic Peninsula. There were some breeding at Fort Point, and some were interspersed in the large Gentoo Penguin colony. A short distance offshore, there was a small chunk of ice with an inclined surface. The Gentoos and the Chinstraps appeared to be playing a game of king of the hill. When penguins come out of the water, they look a bit like the Kramer character on Seinfeld coming into a room. They take a flying leap and land feet first. Both species of penguins did this. Sometimes, they would leap directly into another penguin, causing both to tumble down the slope and into the water. Others fell into the water without being hit by another penguin. At the moment when they are about to fall, they wave their flippers as if falling uncontrollably. The contest was not between the Chinstraps and the Gentoos, but rather a free-for-all, with every penguin for itself. No food was on the chunk of ice, so it is not clear that any of this was being done for any reason other than the sheer fun of it.

Chinstrap and Gentoo Penguins - Photo by William Young

Chinstrap and Gentoo Penguins - Photo by William Young Chinstrap Penguin - Photo by William Young

Chinstrap Penguin - Photo by William Young Chinstrap Penguin - Photo by William Young

Chinstrap Penguin - Photo by William Young Chinstrap Penguin - Photo by William Young

Chinstrap Penguin - Photo by William Young Chinstrap Penguin - Photo by William Young

Chinstrap Penguin - Photo by William Young Chinstrap Penguin - Photo by William Young

Chinstrap Penguin - Photo by William YoungTwo species of penguins had a crest of yellow feathers over their eyes. The larger was the Macaroni, named after the same European characters who were mentioned in the Yankee Doodle song. They have a large heavy red bill and red feet. The only place where we saw a small colony was at Hercules Bay in South Georgia. We observed them from a zodiac. One Chinstrap was in the group. Slipping on the rocks and being out of control seemed like fairly normal behavior for them. We also saw some at sea.

Macaroni Penguins - Photo by William Young

Macaroni Penguins - Photo by William Young Macaroni Penguins - Photo by William Young

Macaroni Penguins - Photo by William Young Macaroni Penguins - Photo by William Young

Macaroni Penguins - Photo by William YoungSouthern Rockhopper Penguins are the smallest penguin species we saw on the expedition. Their crest is not as pronounced as the Macaroni's. We saw a colony of about 2,000 on Saunders Island in the Falklands. As with many penguin species, they form crèches for their young. It is easier to protect the young from skuas and other predators if all of the young are in a group surrounded by adults. The young are furry brown with white underparts. The bill is red, and the feet are pink with black nails. They get their name from hopping on rocks. They seem to be more careful when doing this than the Macaronis. The major predator at the colony appeared to be Striated Caracaras, and I saw some eating the remains of a penguin chick. Jim said the Rockhopper colony we saw was significantly diminished from what it had been. There does not seem to be enough food, perhaps because of climate change and overfishing.

Southern Rockhopper Penguin - Photo by William Young

Southern Rockhopper Penguin - Photo by William Young Southern Rockhopper Penguins - Photo by William Young

Southern Rockhopper Penguins - Photo by William Young Southern Rockhopper Penguin Colony - Photo by William Young

Southern Rockhopper Penguin Colony - Photo by William Young Southern Rockhopper Penguin Crèche - Photo by William Young

Southern Rockhopper Penguin Crèche - Photo by William YoungWe saw many Magellanic Penguin on our final day at sea. Because of the high winds, we were not able to go through the Beagle Channel during daylight hours when leaving Ushuaia. We returned during daylight hours, and Magellanic Penguins were common. Large flocks were swimming near our ship, including one leucistic one who was tan rather than black. Magellanic Penguins have a broad white crescent that stretches from above the eye to below the chin. They also have a broad white stripe going across their black breast. The bill and feet are black. We saw a small colony on Saunders Island in the Falklands. Some were resting on their bellies near the path. They have bare pink skin around their eyes and at the base of the bill.

Magellanic Penguin - Photo by William Young

Magellanic Penguin - Photo by William Young Magellanic Penguin - Photo by William Young

Magellanic Penguin - Photo by William Young Magellanic Penguin - Photo by William Young

Magellanic Penguin - Photo by William YoungThe Adelies were the most entertaining penguin species. They were the third smallest, larger than the Magellanic and Southern Rockhopper. We did not see any Adelies until we reached the Antarctic Peninsula. They are in the same genus as the Chinstrap and Gentoo. The genus name is Pygocelis, which means "rump tailed." The tail of these penguins is longer and stiffer than in other penguin species. These three are the true Antarctic species, and each has partial feathering over its bill. Adelies are named after Adelie Land, an Antarctic territory named for the wife of a French explorer. They are basically a monochrome bird, with the only traces of color being their pinkish nostrils, pinkish feet (with black nails), and an eyering that can look either white, pale blue, or lavender depending upon the way the light hits it. The eyering gives them an appearance of constant astonishment. Only the adults have the eyering. The plumage of the sexes is the same, and Conrad Field, one of the ship naturalists, said that banders sex them by looking for footprints on the back. He also said to examine what Adelies eat, researchers get them to puke into a bucket. I asked him how one induces this, and he said you pour a half a cup of saltwater down the throat.

Adelie Penguin - Photo by William Young

Adelie Penguin - Photo by William Young Adelie Penguins - Photo by William Young

Adelie Penguins - Photo by William Young Adelie Penguins - Photo by William Young

Adelie Penguins - Photo by William Young Adelie Penguin - Photo by William Young

Adelie Penguin - Photo by William Young Adelie Penguin - Photo by William Young

Adelie Penguin - Photo by William Young Adelie Penguin - Photo by William Young

Adelie Penguin - Photo by William Young Adelie Penguin Feet - Photo by William Young

Adelie Penguin Feet - Photo by William Young Adelie Penguin Chick - Photo by William Young

Adelie Penguin Chick - Photo by William Young Adelie Penguin Chick - Photo by William Young

Adelie Penguin Chick - Photo by William Young Adelie Penguin Crèche - Photo by William Young

Adelie Penguin Crèche - Photo by William Young Adelie Penguin Crèche - Photo by William Young

Adelie Penguin Crèche - Photo by William Young Adelie Penguin Adult with Chick - Photo by William Young

Adelie Penguin Adult with Chick - Photo by William Young Adelie Penguin Adult Feeding Chicks - Photo by William Young

Adelie Penguin Adult Feeding Chicks - Photo by William Young Adelie Penguin Adult Feeding Chick - Photo by William Young

Adelie Penguin Adult Feeding Chick - Photo by William Young Adelie Penguin Adult Feeding Chick - Photo by William Young

Adelie Penguin Adult Feeding Chick - Photo by William Young Adelie Penguin Adult Feeding Chick - Photo by William Young

Adelie Penguin Adult Feeding Chick - Photo by William Young Adelie Penguin - Photo by William Young

Adelie Penguin - Photo by William YoungPaulet Island has an estimated 100,000 breeding pairs of Adelies. When an adult Adelie finishes feeding young, it runs away, and the young chase after it. Sometimes, both fall in the chase as they scramble over rocks. When they move forward on ice, they often mix waddling on their feet with tobogganing on their stomach. They sometimes travel considerable distances on their stomachs. Other penguin species toboggan as well. Skuas, sheathbills, Kelp Gulls, and giant petrels were in the Paulet Island colony. We saw a couple of skuas killing chicks, and there were quite a few dead chicks in the area. At one point near where the zodiacs departed, Michael and I were walking down a hill when an Adelie was feeding a youngster a few feet away. We both froze. I was so close I could see the barbs on its tongue when it opened its mouth. At one point, another inquisitive Adelie came by and wanted to peck at Michael's trousers.

AlbatrossesWe were at sea for about 16 days, and albatrosses were fairly common for most of the trip. The most widespread was the Black-browed, which is one of the smaller ones, or mollymawks. It is still a large bird, being a similar size to a giant petrel. The adult's head and underparts are white, and the tip of the tail is black. The upperwings are black from wingtip to wingtip. The underwings are white with a black leading edge and trailing edge. The edges do not continue across the breast, and the leading edge looks slightly broader than the trailing edge. The bill on the adult is pinkish-yellow, and if you look closely, it has a dark pinkish wash near the tip. Young birds have a dark bill, and their underwings look mostly dark. The adults have a dark eyebrow that makes their face look severe, as if they are permanently squinting.

On our first morning out of port, we saw thousands of Black-browed Albatrosses. Some followed our ship, hoping that the churning of the water would stir up food. As we entered the Beagle Channel at the end of the trip, the ocean was calm, and we saw large groups of them sitting on the water, along with a lot of Sooty Shearwaters and Magellanic Penguins. When they take off from the water, they run for about ten steps along the surface before becoming airborne. We visited one of their nesting colonies on Saunders Island. They nest on the ground, and the nests look like a small mud chimneys. One albatross picked up soil in its bill and threw it over its shoulder. It might have been a younger bird practicing nest building. The downy chicks are light gray with a black eye and black bill. They lack the eyebrow, but they have a thin black line running under the eye from the base of the bill. There was only one chick per nest. When leaving on the zodiac from Saunders Island, we were down at the level of the flying albatrosses who skimmed over the waves, and we were able to look up at them from underneath.

Black-browed Albatross - Photo by William Young

Black-browed Albatross - Photo by William Young Black-browed Albatross Colony - Photo by William Young

Black-browed Albatross Colony - Photo by William Young Black-browed Albatrosses - Photo by William Young

Black-browed Albatrosses - Photo by William YoungThe Gray-headed Albatross is a mollymawk who resembles the Black-browed. Its head is gray instead of white, and its bill is black with a yellow edge along the top and bottom. The underwing is slightly different. I saw probably about ten during the trip. They sometimes would come close to the boat, but most of the ones I saw were flying away from the boat. On our final day at sea, I saw what I thought was a Gray-headed who flew close to the back of the ship. Michael later looked at photos and determined that it was a Buller's Albatross, who is very similar.

The Light-mantled Albatross, who used to be called the Light-mantled Sooty Albatross, is a delicate looking bird with long thin wings. The back is a lighter brown than the wings. We saw some flying around the ship, and I also saw one sitting on the water. People who went on the Shackleton hike saw one on a nest. I saw a nest on a distant cliff face when we were at Prion Island. I also saw a couple flying around the cove at Hercules Bay, and I saw more when I was alone at the back of the boat near Stromness. They are lighter colored than both the White-chinned Petrels and the young giant petrels. They look grayish from a distance, and one needs to get a close look at them to appreciate the subtlety of their brown-and-tan plumage.

Wandering Albatrosses were fairly common in some places. One day, some were flying directly over our ship, relatively low. On a day in the Drake Passage, I watched five trailing in the wake. The Wandering goes through numerous plumages on the way to adulthood, and within this group of five, I saw four different plumages. There was a Black-browed Albatross flying with them, which showed how much larger the Wandering is — the wingspan of the Black-browed is 7 to 8 feet, compared to the Wandering whose wingspan is 10 to 12 feet. The adult Wandering has an all white body, and a way to separate them from the similar adult Royal Albatross is that the Wandering always has some black on the tail, even if it is only a few small feather tips. Most of the front of the upperwings is white, while the back of the wing to the tip is black. The underwings are mostly white, with black wingtips and a black trailing edge. The bill is pinkish. Albatrosses have a small tube on each side of their long bill for excreting salt, while storm-petrels and some of the other seabirds have one tube in the middle. If one gets a close look at the adult Wandering, there is a mustard yellow swatch behind the eye. Younger birds have more black on the wings, and some have all black upperwings. Birds who are in their second year still have some brown plumage on their body and head. Their face looks much more serene than the face of the Black-browed. We visited an area where they nest at Prion Island in South Georgia. The nest was on the ground and was made of mud and grass, woven together to form a small bowl. One of the albatrosses was doing nest maintenance. The nest was near the top of what looked like a ski slope going down toward the water. Giant petrels were nesting in the area also, and both of these large species use the ski slope to run down and become airborne. The large albatrosses such as the Wandering spend most of their time soaring in the wind, and they must make a considerable effort to get off the ground. A reason they are not found in more northerly latitudes is that they were not able to become airborne in the area of the ocean known as the doldrums, which had little wind.

Wandering Albatross - Photo by William Young

Wandering Albatross - Photo by William Young Wandering Albatross at Nest - Photo by William Young

Wandering Albatross at Nest - Photo by William YoungIt is sometimes not easy to separate a Royal Albatross from a Wandering. The Royal has a white body in all plumages. It lacks the yellow swatch behind the eye, and its pink bill has a thin black line separating the upper and lower mandibles. Its tail is always all white. The appearance is otherwise similar to a Wandering. Separating Northern and Southern Royal Albatrosses is quite difficult. We studied one large albatross who had a white leading edge to the wing. The upperwings were all dark with no white. We decided it was a Southern, because there was no black feathering in the carpal region. I watched a Royal Albatross one day with Jim whom he called a Northern, but I could not have identified it on my own.

On our first morning at sea, the sky was filled with seabirds, including huge numbers of albatrosses. After awhile, it required an effort not to become blasé about seeing them. I had to remind myself, "I'm looking at albatrosses" and I don't get to do this every day"

Petrels and relativesThe bulk of our birdwatching on the expedition was from the ship. The largest group of birds we observed were the petrels and their allies, which also included the prions, shearwaters, fulmars, and giant petrels. They ranged in size from birds who were the size of mollymawks to birds who were little larger than swallows.

The giant petrels are large and look a bit like dodos when they are on the ground or the ocean. There are considerable differences in plumage by age, with the young birds being dark brown and the older ones becoming lighter. They are scavengers, and someone giving a talk showed a photo of two of them with blood all over their heads after eating a dead seal. Unlike vultures who have lost their head feathers in an effort to stay clean, giant petrels can dip their bloody head into the water. Some of them nest in penguin colonies so that they can be close to their food source. When on the ground, they sometimes spread their wings and stomp around with their tail upraised in a threat posture to defend a carcass, almost like an enraged rooster. They had a crazed and diabolical look in their eyes — they also looked this way in the photo with the blood-soaked heads. The Northern and Southern Giant Petrel can be difficult to tell apart. The best fieldmark is that the Southern has a green tip to the bill, while the tip of the Northern's is reddish purple. I had trouble seeing this unless I saw a bird flying close to the ship in good light. The Southern has an all-white color morph known as a White Nelly. We moved close to one on our zodiac ride from Saint Andrews back to our ship. The bird was sitting placidly in the water. As the zodiac approached, it did not fly away, but it seemed to intentionally position itself so that its back was to us, as if it were trying to snub us. Giant petrels often followed our ship. I once saw a pair of Northern Giant Petrels engaged in courtship behavior, flying together and stretching their necks. Near the Falklands, I saw a Brown Skua and giant petrel going after each other. At Prion Island, I saw one use the same runway to the ocean that the Wandering Albatrosses used. And at Saint Andrews, we saw a giant petrel whitewater rafting like the King Penguins.

Northern Giant Petrel - Photo by William Young

Northern Giant Petrel - Photo by William Young Northern Giant Petrel - Photo by William Young

Northern Giant Petrel - Photo by William Young Northern Giant Petrels - Photo by William Young

Northern Giant Petrels - Photo by William Young Northern Giant Petrel Chick - Photo by William Young

Northern Giant Petrel Chick - Photo by William Young Northern Giant Petrel at King Penguin Colony - Photo by William Young

Northern Giant Petrel at King Penguin Colony - Photo by William Young Southern Giant Petrel "White Nelly" - Photo by William Young

Southern Giant Petrel "White Nelly" - Photo by William YoungThe White-chinned Petrels were the next size down from the giant petrels. Their plumage is the color of dark chocolate, and they have a cream-colored bill. It is very difficult to see the white chin on the birds when they are flying. Some followed our ship and flew in long looping figure-8 circuits. We saw a White-chinned Petrel who appeared to have a dark bill. I asked Jim Wilson, the on-board ornithologist, if the young ones have dark bills, and he said no, but they sometimes have dark edges on their bill. I looked at photos of the bird with John, and it indeed had dark edges on a light bill.

White-chinned Petrel - Photo by William Young

White-chinned Petrel - Photo by William YoungSooty Shearwaters are all dark and smaller than White-chinned Petrels. They are the color of milk chocolate, and they have light feathering on their underwings. Like the White-chinned Petrels, they soar in the wind, often dragging one wingtip near the edge of the water. On our last day at sea, we saw thousands of Sooty Shearwater while we were in the Beagle Channel. Many were sitting on the water, which was calm. As with the Black-browed Albatrosses, they need about ten steps of running along the water to become airborne. In the Drake Passage, some Short-tailed Shearwaters were mixed in with the Sooty Shearwaters, but they are extremely difficult to separate, even with a photograph. We saw quite a few Great Shearwaters in the Drake Passage. They are relatively easy to identify, because they have white underparts, a dark cap, and a white collar. They are larger than the Sooty.

The Kerguelen Petrel is another all dark seabird. It is named after the Kerguelen Islands in the southern Indian Ocean. Exactly one was seen on the trip, and its sighting was an example of Michael's incredible birding skills. We had just left South Georgia and had begun our trip to the Antarctic Peninsula. It was getting dark, light snow was falling, and fog was setting in. It was also cold and windy, so Michael, Paul, John, and I (the only people still on deck looking at birds) decided to call it a night. We stepped inside the door, and before we headed to our rooms, Michael and John wanted to do a list of sightings. As they were talking, Michael saw something out of the corner of his eye and said that it was a good bird. We all rushed outside, and he got all of us on the Kerguelen Petrel, who was a couple of hundred yards away. The bird was a little smaller than a Sooty Shearwater and appeared to have longer, narrower wings. Its flight also seemed more direct than the Sooty Shearwater and White-chinned Petrel. Considering the poor level of light and visibility, the distance of the bird, and the fact that we were inside doing something else, Michael's sighting was pretty amazing.

Three of my favorite seabirds of the trip were the Snow, Antarctic, and Cape Petrels. The Snow Petrel is an immaculate white bird (the "angel of the Antarctic") with a black bill and black eyes and feet. For a monochrome bird, it is stunning. A number of them flew close to our boat, and we began to see them as we approached South Georgia. I climbed a hill at Brown Bluff to see one on a nest in a cave. Antarctic Petrels were not seen often. The only ones I saw were a group of about 40 as we approached the Antarctic Peninsula. They were behind an iceberg, and they all of them suddenly flew right over our ship. Apparently, they kept flying when they reached the other side of the ship. The front half of their upperwing is dark, while the back half is white. From below, they look like a larger version of a Cape Petrel, with white underparts and a black hood and throat.

The Cape Petrel has black wings that look as if Jackson Pollock spattered them with white paint. This painted appearance is responsible for their other name of Pintado Petrel, which comes from the Spanish word for paint. Pinto horses are named from the same word, and it is why cowboys used to call some of their horses "old paint". I called the Cape Petrel the "anagram bird". The scientific name is Daption capense, with Daption being an anagram of pintado. One day as we were approaching the Antarctic Peninsula, there were about 5,000 Cape Petrels who flew by our cabin window at porthole level. I don't think they were circling the boat, and they appeared to be flying from the front to the rear. Sometimes, more than a dozen would be in view at once. From the early morning to the late afternoon, they streamed by. The numbers declined substantially the following day, but some were still around. When we were in a zodiac near Paulet Island, I saw three swimming placidly in the calm water. Paul said he had been in a zodiac when a Cape Petrel misjudged a landing and landed in the bottom of the zodiac. It was picked up and released.

Cape Petrel - Photo by William Young

Cape Petrel - Photo by William Young Cape Petrels - Photo by William Young

Cape Petrels - Photo by William Young Cape Petrels - Photo by William Young

Cape Petrels - Photo by William Young Cape Petrels - Photo by William Young

Cape Petrels - Photo by William YoungWe started to see Southern Fulmars as we approached the Antarctic Peninsula. The name "fulmar" means "foul gull", because if they are harassed in their breeding area, they will projectile vomit a foul substance. They look like a medium-sized gull whose outer wings are black with a large white patch. I remember seeing Northern Fulmars whose wings looked farther back on the body than the wings of a gull, but the Southern ones did not convey this appearance. They often flew close to the boat. I saw some adults, who are mostly white, and some younger birds who are darker.

Southern Fulmar - Photo by William Young

Southern Fulmar - Photo by William YoungPrions are difficult to identify. They are small seabirds, about ten inches long, and their flight is rapid and twisting. To identify them, one needs to look closely at the face pattern, bill shape, and tail. Coming out of Ushuaia, most of the ones we saw were Slender-billed Prions. One day, we saw about 4,000 of them. Later in the trip, we saw mostly Antarctic Prions, who do not have as prominent an eye stripe and seem to have a larger smudge on their neck. Both of these species have a black M pattern on their dark gray back. The pattern is darker on the Antarctic, but this can be difficult to see in the field. Mixed in were a few Fairy Prions, who have a less distinct face pattern than the Antarctic, a smaller bill, and more black on the tail. We saw one of these sitting on the water like a phalarope. A bird who looks like a prion is the slightly larger Blue Petrel. It is fairly easy to identify, because the tip of its tail is white rather than black. We saw a lot of these in the seas near the Antarctic Peninsula. The head pattern also looks a lot darker than the prions. The only other bird I saw in this family was the Soft-plumaged Petrel, who is larger than the Blue Petrel. It is distinctive because of its white body and dark underwings. It had a strong, arcing flight.

Antarctic Prion - Photo by William Young

Antarctic Prion - Photo by William Young Antarctic Prions and Cape Petrel - Photo by William Young

Antarctic Prions and Cape Petrel - Photo by William Young

Diving PetrelsThere are three species of diving petrels in the areas we visited. I never got a close look at any of them. They are small seabirds resembling a Dovekie. The ones I saw were flying at a distance, fast and low to the water. At times, they appeared to disappear into the waves. I saw what was probably a Common Diving Petrel as we were nearing the Falkland Islands. The Common is very similar to the South Georgia Diving Petrel. Jim Wilson said the two species cannot be told apart unless in the hand — the South Georgia has a black line on the tarsus. When we were in the Beagle Channel, we saw one whom Michael identified as a Magellanic. It can be told from the other two by its white collar. I did not see that, but Michael was able to see it in a photo he shot of the bird, and this species was the only one of the three likely to occur in the area.

Storm-PetrelsMost of the storm-petrels I saw were Wilson's. They are all black above and below, with a white rump. On some days, there were a great many of them, and I saw quite a few pattering near the ship. Sometimes, they fly like bats. On Prion Island when we were looking at the nesting Wandering Albatrosses, a Wilson's Storm-Petrel was fluttering around our heads — it probably had a nest nearby. This species nests in rock crevices or in burrows. We also saw storm-petrels flying in front of rock faces, possibly because they nested there. Once we left the Falklands, we began to see Black-bellied Storm-Petrels, who are slightly larger and longer winged. They sometimes drag a foot or a wing in the water when they are near the surface. They have a white belly, and they are so named because there is a black line running down the middle of the belly, which can sometimes be seen when the bird banks in flight. From the back, they looks like Wilson's. Once, I saw the two species together, which provided a good size comparison. Someone found a Wilson's who had landed on the deck of our ship one night, and it was let go the next morning. We were told to keep our windows sealed to prevent storm-petrels and other birds from being confused by the lights of our ship as we passed. Diving-petrels were also found on the deck, and I'm sorry I did not have a chance to see one in the hand. I did not manage to see a Gray-backed Storm-Petrel. A few were mixed in with the Wilson's, usually on floating kelp beds, but I did not manage to get onto one. Also, in the Beagle Channel, there is a subspecies of the Wilson's called the Fuegean Storm-Petrel, which might at some point be split, but I am not sure if it is possible to positively identify them in the field.

CormorantsAt the South Beach Reserve in Buenos Aires, we saw four Neotropic Cormorants sunning themselves on an island in the water. The range of this widespread species reaches into the United States. At Ushuaia, we saw Magellanic (or Rock) Cormorants, who are dark with a white belly. A pair was nesting on the side of an abandoned ship, and the adults were feeding two chicks. Also in Ushuaia were Imperial Cormorants. They are part of a complex of species who have been split. The ones around Ushuaia are called Blue-eyed Cormorants (Shags). A lot of these were in the water as we went through the Beagle Channel the night we took off, as well as on our trip to Tierra del Fuego. When they flew, they had some white on the upperwings. Around the Falklands, the species is called the King Cormorant. There is a separate species called the South Georgia Shag, and we saw thousands of them perched on Shag Rocks. On Paulet Island, the species becomes the Antarctic Shag, which is endemic to the area. All of these species look pretty much the same but have a different pattern of black and white on the face. I had outstanding views of the Antarctic Shags on Paulet Island. Some were nesting on a rocky hillside, and like the Double-crested, they have blue eyes. They have a yellow knob above the bill. The young are brownish rather than black and white. When we got into the zodiac, we moved close to an iceberg that had both Antarctic Shags and Adelie Penguins. The light was magic, and all of the plumage coloring of both birds looked deeply saturated. The shags have a plumage pattern similar to the penguins, and our zodiac driver said that some visitors get confused when they see birds who look like penguins flying. Jim Wilson (who is from Ireland) told the story about giving a presentation at an Irish school where the children and, sadly, the teachers, thought penguins could fly, because they had seen a 2008 BBC April Fools spoof narrated by Terry Jones of Monty Python in which penguins take to the air and fly to the tropics. At Fort Point, one of the Antarctic Shags began walking quickly toward me. I'm not sure I had ever seen a cormorant walk any significant distance before. It had large dark pink feet that looked dirty.

Imperial Cormorant - Photo by William Young

Imperial Cormorant - Photo by William Young South Georgia Shags on Shag Rocks - Photo by William Young

South Georgia Shags on Shag Rocks - Photo by William Young South Georgia Shags - Photo by William Young

South Georgia Shags - Photo by William Young Antarctic Shag - Photo by William Young

Antarctic Shag - Photo by William Young Antarctic Shag - Photo by William Young

Antarctic Shag - Photo by William Young Antarctic Shag with Adelie Penguins - Photo by William Young

Antarctic Shag with Adelie Penguins - Photo by William Young Antarctic Shag with Adelie Penguins - Photo by William Young

Antarctic Shag with Adelie Penguins - Photo by William Young

HeronsIn Buenos Aires, we saw a Whistling Heron in a wetland at Otamendi. It has a grayish body with a black-tipped red bill and a blue face. At the South Beach Reserve, we saw a Striated Heron, who is like a striped Green Heron, shortly before we boarded the bus to return to our hotel. It was standing in the water, and I took photos of it with its reflection in the late afternoon light. Earlier in the day, I had photographed a Rufescent Tiger-Heron who flew into a marsh and perched obligingly. There were Cocoi Herons, who look like Great Blues, as well as Great, Snowy, and Cattle Egrets. At Tierra del Fuego, we saw an immature Black-crowned Night-Heron. This species is very widespread. I saw a bunch of them in Tanzania.

Whistling Heron - Photo by William Young

Whistling Heron - Photo by William Young Striated Heron - Photo by William Young

Striated Heron - Photo by William Young Rufescent Tiger-Heron - Photo by William Young

Rufescent Tiger-Heron - Photo by William Young

VulturesThere were a few Turkey Vultures soaring over Ushuaia. I was in a bus when we saw them, so I could not see if they were different from the ones in our area. At Tierra del Fuego, we saw two soaring Andean Condors. They were so high that it was difficult to see any detail on the plumage, but the shape was distinctive. Some people in Buenos Aires saw Black Vultures, but I did not.

Hawks and EaglesWe did not see many hawks and eagles on the trip. There were three species at Otamendi. We saw a soaring Snail Kite. I used to think these were rare birds because they are so uncommon in the US, but they are fairly common in Central and South America. We saw a perched Roadside Hawk, and I later saw one flying. And we saw both a light morph and dark morph Long-winged Harrier, who have long wings and a light rump. In Ushuaia, John spotted a pair of Black-chested Buzzard-Eagles while we were at a reception. They have a short tail, white shoulders, and broad wings. Even though I did not have my binocular, I managed to get good looks.

SheathbillThe Snowy Sheathbill looks like a white football. Unlike the Snow Petrel and the male Kelp Goose who are also all white, the Snowy Sheathbill looks more dirty white than clean white. It looks a bit like a pigeon when it flies. It has bare pink skin on its face and what looks like a scabby crust over its bill and on its feet. It can walk fairly quickly over rocks, and it always seems to be lurking for some opportunity to pick up something to eat. It is not as ominous as a skua or giant petrel, but it has similar aspirations. For the first part of the trip, I saw them from a zodiac and did not have a chance to photograph one. I also did not see one close up at the King Penguin colony at Saint Andrews. But I managed to get close to a few at Paulet Island. One of the zodiac drivers called them Snowy Shitbills, which seems appropriate.

Snowy Sheathbill - Photo by William Young

Snowy Sheathbill - Photo by William Young Snowy Sheathbill - Photo by William Young

Snowy Sheathbill - Photo by William Young

OystercatchersA pair of Blackish Oystercatchers were at the park in Tierra del Fuego. They look like a standard black oystercatcher with a bright red bill. I saw a similar species in Australia, and we looked for them on black rocks by searching for the red line that was the bill. I am not sure why they are called "blackish" rather than "black". A pair of Magellanic Oystercatchers was on the beach at Saunders Island, and one appeared to be on a nest. It is a standard black-and-white oystercatcher. I would have tried to walk closer to it, but the wind was intense.

PloversThe only plovers we saw were Southern Lapwings. We saw a lot of them in the mowed grassy areas we drove past in Buenos Aires. There were also some by the water in Ushuaia. A couple of the Ushuaia birds seemed to have a nest near the water, because they became agitated as our group approached.

Southern Lapwing - Photo by William Young

Southern Lapwing - Photo by William Young

ShorebirdsOne of the only shorebirds I wanted to see was a Baird's Sandpiper. They occur on the bottom tip of South America. I was in the lounge with Michael on the morning our ship was stuck in the port at Ushuaia because of the high winds. I decided to go back to my room, and shortly after I left, Michael saw a Baird's Sandpiper trying to fly into the wind, so he got a good look. It is a jinx bird I have never seen, and no other ones were seen on the trip. At least I won't have to return to bottom of the world to see one like the people who missed the Falkland Steamer Duck.

SkuasThis trip provided my first experience of seeing a lot of skuas up close. Roger Tory Peterson talked about skuas in penguin colonies operating a protection racket: they eat their share of penguin chicks and eggs, but because they are territorial, they chase away other skuas and prevent the entire colony from being destroyed. The skuas on this trip all looked pretty much alike — stocky brown birds with white marks near the ends of their wings. There were differences in the shade of brown, the bulkiness of the bird, and whether there was a dark cap.

The Chilean Skuas in Ushuaia have a black cap and plumage that looks cinnamon colored in good light. Later in the trip, I saw Brown Skuas, who look darker, bulkier, and stronger than the Chilean. One who was near a penguin colony in the Falklands was standing close to an egg, and it was not making an effort to peck at the egg or eat it. At Saint Andrews, I saw an adult with two chicks who were begging for food. The nest was near the penguin colony. Michael thought that one of the skuas we saw at Saint Andrews might have been a hybrid, because it looked smaller and did not have as much mottling as some of the other Brown Skuas. At Gold Harbor, I watched as one took a bath in the water that was surrounded by King Penguins, Southern Elephant Seals, and Antarctic Fur Seals. At Hardy Cove in the South Shetland Islands, I saw four South Polar Skuas perched on rocks at the top of a hill. They are noticeably smaller than the Brown Skuas. One was a pale morph and looked blondish. The weather was overcast, so I could not see the color in good light. At Paulet Island, I saw a skua killing a live Adelie chick. I know it is part of the natural food chain, but it is still difficult to watch.

Chilean Skua - Photo by William Young

Chilean Skua - Photo by William Young Brown Skua - Photo by William Young

Brown Skua - Photo by William Young Brown Skua - Photo by William Young

Brown Skua - Photo by William Young Brown Skua - Photo by William Young

Brown Skua - Photo by William Young Brown Skua Chick - Photo by William Young

Brown Skua Chick - Photo by William Young Brown Skua - Photo by William Young

Brown Skua - Photo by William Young Falklands Brown Skua - Photo by William Young

Falklands Brown Skua - Photo by William Young Falklands Brown Skua - Photo by William Young

Falklands Brown Skua - Photo by William Young South Polar Skuas - Photo by William Young

South Polar Skuas - Photo by William Young South Polar Skua - Photo by William Young

South Polar Skua - Photo by William Young South Polar Skua Eating Adelie Penguin Chick - Photo by William Young

South Polar Skua Eating Adelie Penguin Chick - Photo by William Young